Between 1963 and 1975, WED Enterprises were on top of their game with attractions like it’s a small world, The Enchanted Tiki Room, Adventure Thru Inner Space, Pirates of the

Between 1963 and 1975, WED Enterprises were on top of their game with attractions like it’s a small world, The Enchanted Tiki Room, Adventure Thru Inner Space, Pirates of the

“There was a bit of jealousy there… Walt bought what he [Marc] did and he never bought what they did.” – Alice Davis

Note: I am assuming the readers are familiar with “Country Bear Jamboree” and “America Sings”, as this is an analysis, not a history. Those of us who don’t listen to these shows constantly may want to take a “refresher course” in the form of music or video (of varying degrees of legality) that may (or may not) be available online.

“He’s big around the middle and he’s broad across the rump

Runnin’ 90 miles an hour, takin’ 40 feet a jump

Ain’t never been cornered, ain’t never been treed.

Some folks say looks a lot like me.”

One of the original

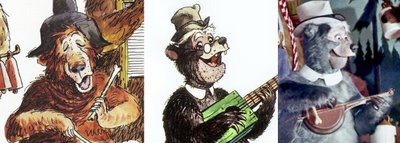

This was a Marc Davis show from beginning to end.

Davis' art, matched very closely by WED Enterprises.

“character work”. Although the bears in Country Bear Jamboree are often stylized in such a way so that you can immediately understand their personality from first glance, they also are involved in developing action: the bears are not, in short, gags in and of themselves.

“character work”. Although the bears in Country Bear Jamboree are often stylized in such a way so that you can immediately understand their personality from first glance, they also are involved in developing action: the bears are not, in short, gags in and of themselves.

This is taken one step further in the Bear show.  ly turn off once their number has been completed. We naturally fill in the blanks: where they’re from, how they got here, what they ate for lunch, etc. This is a triumph of artifice in the extreme sense: we’re not even reacting to humans up on stage, but exaggerated versions of them in the forms of bears! Singing bluegrass!

ly turn off once their number has been completed. We naturally fill in the blanks: where they’re from, how they got here, what they ate for lunch, etc. This is a triumph of artifice in the extreme sense: we’re not even reacting to humans up on stage, but exaggerated versions of them in the forms of bears! Singing bluegrass!

But the world’s illusion is total, from the macro (the Grizzly Hall “backwoods Victorian” setting) to the micro (the entrance hall’s floorboards are scuffed with bear claw marks). Ollie Johnson and Frank Thomas wrote of the “illusion of life” in their famous animation volume.

The drive of the show to resolve the rhythmical, building force of the songs: for about seven minutes there are five uninterrupted acts which build in rapidity and intensity, wavering between male and female acts, solo and ensemble acts, which build a cumulative total effect of having been seeing a real live performance. This is where the Vacation Hoedown version, in particular, fails: it does not trust the audience enough to sit still for about ten minutes of uninterrupted music with no real overt jokes: it is constantly interrupting the flow of the music and performance with asides, gags, mishaps, and other nonsense.

This sense of variety and, foremost, pace is why Bears still entertains but something like The Mickey Mouse Revue in Fantasyland, also a Magic Kingdom opening day show and also a unique Florida attraction, is today a barely remembered and rather tedious curiosity. Mickey Mouse Revue was particularly bad in letting down the rhythm and pace of each number with the next: following “The Three Caballeros” with the crashing bore that is “So This Is Love”. The Bears just don’t let up. On the other side of the equation, The pacing is so careful and succinct that although each number lasts only a few minutes at most, they’re adequately allowed to breathe so that Bears doesn’t have the effect of, whatever their merits or failings, Stitch’s Great Escape or Mickey’s Philharmagic, where the makers seemed to chafe at the idea of allowing any action to play for more than 15 seconds without having the hit the audience with a new “gag”

This sense of variety and, foremost, pace is why Bears still entertains but something like The Mickey Mouse Revue in Fantasyland, also a Magic Kingdom opening day show and also a unique Florida attraction, is today a barely remembered and rather tedious curiosity. Mickey Mouse Revue was particularly bad in letting down the rhythm and pace of each number with the next: following “The Three Caballeros” with the crashing bore that is “So This Is Love”. The Bears just don’t let up. On the other side of the equation, The pacing is so careful and succinct that although each number lasts only a few minutes at most, they’re adequately allowed to breathe so that Bears doesn’t have the effect of, whatever their merits or failings, Stitch’s Great Escape or Mickey’s Philharmagic, where the makers seemed to chafe at the idea of allowing any action to play for more than 15 seconds without having the hit the audience with a new “gag”

Davis and Bertino perfectly pace out the short numbers with instrument solos and variations; the effect is of the bears actually having to keep time and rhythm. In effect, this central segment of the show is what the bears have been trying to achieve in the first five acts and have been thwarted by the sarcastic animal heads. Each act significantly ups the ante of the previous. Once Teddi Barra’s swing number is over, the show has, in effect, no place to go once Big Al appears and sings his dreadful version of Blood on the Saddle. Henry and Sammy attempt to almost immediately recover the rhythm of the pre-Big Al material, but once Al (irrationally) returns for another solo, he threatens to disrupt the driving force of the music for, if the rhythm is offset, the show must, by definition, be over. This is why all the other bears team up to drown him out and prevent the building rhythm and structure of the music towards reaching its logical conclusion: once the pace is gone, the revue is essentially “dead in the water”. The show is structured so that the bears must fight to continue to have the attention of the audience. Just like in the vaudeville routines of the day, losing audience sympathy will result in being pulled offstage with a hook, ending the act and, by extension, the show.

Yet ironically the resolution of this conflict is also the resolution of the show itself for, once all the members of the Bear Band perform together, there is no further spectacle that can be provided by the troupe and the audience must be shuffled out the door, always with the requisite Southern hospitality: “ya’ll come back now, y’hear?”

Aside from the rhythm and pace, the second aspect the later shows seriously fudge is the characters themselves. Only Henry, Max, Buff, Melvyn and the Sun Bonnets seem to be the same characters: for no reason Liver Lips McGrowl becomes an Elvis rock and roll style character, which so badly misjudges the point of Liver Lips in the original show its offensive. The “thesis statement” of the show is stated by Henry almost immediately at curtain up: “A bit of

Aside from the rhythm and pace, the second aspect the later shows seriously fudge is the characters themselves. Only Henry, Max, Buff, Melvyn and the Sun Bonnets seem to be the same characters: for no reason Liver Lips McGrowl becomes an Elvis rock and roll style character, which so badly misjudges the point of Liver Lips in the original show its offensive. The “thesis statement” of the show is stated by Henry almost immediately at curtain up: “A bit of

A similar turnaround happened with Trixie, who gained a “big voice” with lots of gospel-style range. But the whole point of Trixie is that she’s enormous but has a tiny little voice and a petite attitude. However, most irritatingly of all, Teddi Barra was unsexed in all later versions of the show: giving her a rain slicker or cast makes the joke of a sexy bear on a floral swing rather beside the point. Worse, she was stripped of her accent, replacing those charming flat vowels with a rather bland and sweet non-regional accent. Where are these bears from, again?

When is this supposed to be happening, again? The date on Grizzly Hall in The Magic Kingdom reads late-19th century and the structure looks rather like Great Northwest territory colonial dance halls. The show inside is split between appearing in this kind of setting and having regional Floridian references thrown into the mix (the Tampa Temptation; The Vibrating Wreck From

What is certain is that modern songs and references are outside of the realm of the attraction, although arguably Disney has been consistently breaking the Fourth Wall ever since cacti dressed up to look like the Seven Dwarfs appeared on the Rainbow Ridge Mine Trains in 1956. Still, the incongruity of these characters singing “Thank God I’m A Country Boy” or “Singing in the Rain” is transparent, in addition to removing half the ostensible purpose of Country Bears and America Sings – to expose the audience to kinds of music outside of their day-to-day experience. The Vacation Hoedown really just confirms the audience’s probably modern and narrow definition of “country music” in grand fashion. In the 90’s this kind of pandering even gained new speed in Imagineering as a proposed attraction transforming the bears into caricatures of modern country stars made the rounds. This tasteless idea was thankfully shot down with assured finality by that decade’s close and the failure of “hip” attractions like The Enchanted Tiki Room: Under New Management.

The things Disney will sink money into…

Thankfully the bears still play on in The Magic Kingdom. Disneyland’s closure of their version and the drama surrounding it is well recorded elsewhere and will serve no purpose to repeat it here, suffice to say that in some ways Disney shot themselves in the foot while simultaneously trying to jump the gun by placing the bears way back behind the Haunted Mansion, out of any sane traffic flow, in the beautiful but usually vacant Bear Country. Placed right in the path of most guests,

In the mid-90’s some of the bears were reprogrammed to negative effect in

Return next week for the conclusion of this article.