Walt Disney World is full of hidden history - experiments that didn't last, ideas that didn't make it, things that have either forgotten about or totally elided. These are, of course, the areas that the intrepid Walt Disney World researcher seeks to illuminate, but more often than not she's going to find herself at some opaque but inevitable dead end. Sometimes, however, a pattern begins to emerge, and today we're going to plunge very deeply into speculation and informed guessery. Sadly the decisions which shaped the history of the Magic Kingdom are largely not recorded or, if they are recorded, they're not available to consult. But the evidence speaks loudly. Something very significant happened in the early months of Walt Disney World, something that shaped Disney's design strategies for a very long time, and that something has a lot to do.... with food.

Walt Disney World is full of hidden history - experiments that didn't last, ideas that didn't make it, things that have either forgotten about or totally elided. These are, of course, the areas that the intrepid Walt Disney World researcher seeks to illuminate, but more often than not she's going to find herself at some opaque but inevitable dead end. Sometimes, however, a pattern begins to emerge, and today we're going to plunge very deeply into speculation and informed guessery. Sadly the decisions which shaped the history of the Magic Kingdom are largely not recorded or, if they are recorded, they're not available to consult. But the evidence speaks loudly. Something very significant happened in the early months of Walt Disney World, something that shaped Disney's design strategies for a very long time, and that something has a lot to do.... with food.First, some on the ground reports.

"The theme park... the Magic Kingdom, was built exactly the way Walt Disney always intended it.. [...] We called it "the vacation kingdom of the world". I wrote that slogan, too. Before this, nobody went to Orlando for a vacation... nobody. In the late sixties, we were totally focused on Walt Disney World, of course. The company had made the decision, in late 1967, to go ahead with it. From then on, we just ran as fast as we could, to get that project open. We really didn't have a breather because we had to meet some surprising demands from the public. Buzz Price had originally projected six million people for Walt Disney World's first year. By the time we were really building the Florida site in 1969, Disneyland was already getting eight million a year. We tried to increase the capacity to handle eight million, and we felt a constant pressure during the Florida development. [...] But soon we were doing over ten million the first year alone." - Marty Sklar, The "E" Ticket, Number 30, 1998Now anybody who's been to both Disneyland in California and Walt Disney World in Florida is bound to play the comparison game; in a way it's unfair to both attractions but in another it is indeed invited. Tony Baxter describes it perhaps most charitably when he terms Disneyland "charming" and The Magic Kingdom "spectacular". Although the difference isn't too shocking when comparing strictly acreage - 85 acres versus 107 acres - Disneyland is simply stuffed to the gills with stuff. As a result we find attractions stacked on top of each other, shops wedged strangely into the spaces between and restaurants often filling as much pedestrian space as they dare. Viewed today, especially compared to the cavernous meal spaces regularly offered to Walt Disney World visitors where space is not at a premium, major Disneyland eateries seem more like upgraded snack bars with two dozen extra tables.

"Nearly 40,000 visitors – the biggest crowd yet – jammed Walt Disney World turnstiles Saturday as the $400 million “Magic Kingdom” kicked off its three-day formal opening celebration with the arrival of a plane-load of Hollywood notables. [...] Crowds have increased steadily since the Oct. 1 opening for a three-week “shakedown” for employees and attractions. Opening with 10,400 visitors, the park had averaged around 15,000 daily with 20,000 to 25,000 on the weekends." - Orlando Sentinel, October 24, 1971

"The day after Thanksgiving, traffic ground to a halt ten miles up International Drive. By 2:00 in the afternoon, with thousands of cars crammed in and around its parking lot and 56,000 guests squeezed inside the park, Disney was forced to close the access ramp leading off Interstate 4. All four lanes of traffic slowed to a crawl in both directions, creating a 30-mile stretch of confused, angry motorists. Inside the park, guests had to wait two hours or more to ride the submarines, Country Bear Jamboree, and other top attractions. [...] There were also not enough restaurants nor time to instantly build them. Instead, Disney set up temporary quick-service stands throughout the park. In Fantasyland, a tent-like structure went up to sell hot dogs and hamburgers, and another sold pizza." - David Koenig, Realityland

If we go back in time and think about major food offering at Disneyland in 1971, you basically have the Plaza Pavilion, Coke Corner and Plaza Inn on Main Street, The Tahitian Terrace in Adventureland, The Blue Bayou, Creole Cafe, and French Market in New Orleans Square, the Casa De Fritos, Golden Horseshoe, and Aunt Jemima Kitchen in Frontierland, and then the Captain Hook Pirate Ship in Fantasyland and the Tomorrowland Terrace in Tomorrowland, and none of them are especially huge. Of the twelve mentioned above, five of them are table service restaurants. And of course there were plenty of snack stands and smaller cafes located between as well, like the Hills Brothers Coffee House on Main Street.

--

Now let's compare that to what the Magic Kingdom offered in 1971. There was the Town Square Cafe, Refreshment Corner and Crystal Palace serving Main Street, with the Adventureland Veranda, The Liberty Tree Tavern, King Stephan's Banquet Hall, the Pinocchio Village Haus, and the Tomorrowland Terrace pulling for the rest of the park. Yes, that's about it. In terms of quick service, high capacity locations, the list is even shorter: Adventureland Veranda, Pinocchio Village Haus, and Tomorrowland Terrace.

The Mile Long Bar in Frontierland is listed as being open in an October 1971 Walt Disney World News, but an internal cast publication indicates that it wasn't ready until mid November. Pecos Bill Cafe next door wouldn't be on-line until December, and was therefore of little use to Disney in dealing with those nightmarish Thanksgiving 1971 crowds. Since the same issue of Walt Disney World News makes no mention of the Westward Ho shop next to Country Bear Jamboree, we can assume that it was not ready until later and that the walk from Country Bear Jamboree to the Davy Crockett Explorer Canoes landing was a long walk past seemingly empty facades. Everything West of Country Bear Jamboree was unfinished.

The single restaurant listed for October 1971 in Liberty Square is the Tavern, although Sleepy Hollow Refreshments is listed on late 1971/early 1972 souvenir maps, meaning it may have been accidentally excluded or simply wasn't ready for opening day. The massive multilevel, multikitchen (remember that there was a serving counter upstairs until the late 1980's) Columbia Harbour House would not bow until mid 1972 and hadn't even had her name decided - on an early souvenir map the restaurant is called the Nantucket Harbour House. The Diamond Horseshoe was ready but was not treated as or expected to be used as a restaurant, always listed as an attraction. The sole shop that was ready - the tiny Tricornered Hat Shoppe near Frontierland - stood alone, for the bulk of Liberty Square's shops would not open until early 1972.

Missing from early maps and listings are two fairly significant Fantasyland establishments - Lancer's Inn and The Round Table - walk-up, take out restaurants occupying the space between Snow White's Adventures and Mr. Toad's Wild Ride, meaning this stretch of facades across from the Submarine Lagoon was a possible original home for the Fantasyland Art Festival portrait artists. Lancer Inn and round Table do appear together on early 1973 maps, likely replacing the temporary tents described by Koenig. Instead, a new building near the Mad Tea Party was built to house the portrait artists, until a new juice bar moved in and displaced them once again in 1979. Lancer Inn and Round Table can today be observed in relatively untouched form as Mrs. Potts' Cupboard and The Friar's Nook.

Tinkerbell's Treasures, Merlins Magic Shop and the Aristocats Gift Shop didn't seem to exist, rendering the Cinderella Castle Courtyard another empty stretch of facades. Tomorrowland fared the worst of all, offering only the Grand Prix Raceway, Skyway station, a shop at the base of the Skyway station near the restrooms, and the Tomorrowland Terrace.

Now between 1971 and 1975, when Card Walker declared Phase One of Walt Disney World complete, Disney did indeed add shops and attractions all over the Magic Kingdom... but most of what they added was restaurants. Astonishing numbers of restaurants. Based on the information above and data I've compiled elsewhere, the roster looks something like this:

1972

The Fife & Drum Snack Bar

Columbia Harbour House

The Lunching Pad (inside the Space Port shop)

The Round Table

Temporary outdoor cafeteria near the future site of the Carousel of Progress

1973

1973Lancer Inn

Aunt Polly's Dockside Inn

Cantina (inside the fort on Tom Sawyer Island)

1974

El Pirata y el Perico snack stand

The Plaza Restaurant

The Plaza Pavilion (bridging Tomorrowland and Main St. on the south side)

1975

The Space Bar (base of the Peoplemover platform)

That's twelve additional food service locations - two of them massive and one offering table service and requiring Card Walker's elaborate Swan Boats to move to a newly built boarding location on the hub. The fact that Disney closed the original Swan Boat Landing and moved the operation of an attraction - one designed explicitly to increase capacity - to make way for a restaurant carved out of the old Borden Ice Cream Shoppe shows where Disney's priorities were.

It's easy to imagine their terror. It can be sensed in Marty Sklar's quote above. WED had given itself five years, in 1969, to exceed attendance of ten million. They succeeded in less than a year. But even worse, the park and resort was stretched to it's maximum almost immediately. Construction on Villas in nearby Lake Buena Vista began in November 1971. In 1972, the tiny clubhouse for the Palm and Magnolia golf courses was already being built out into a 151 room resort. Fort Wilderness expanded in 1974 and the Polynesian in 1978. Restaurants, bars, and dinner shows were added all along the way. It all speaks of a panicked response somewhere in Disney's corporate corridors - call it the Phantom Food Scare of 1971. The evidence is everywhere, except for the evidence of the panic itself.

It's easy to imagine their terror. It can be sensed in Marty Sklar's quote above. WED had given itself five years, in 1969, to exceed attendance of ten million. They succeeded in less than a year. But even worse, the park and resort was stretched to it's maximum almost immediately. Construction on Villas in nearby Lake Buena Vista began in November 1971. In 1972, the tiny clubhouse for the Palm and Magnolia golf courses was already being built out into a 151 room resort. Fort Wilderness expanded in 1974 and the Polynesian in 1978. Restaurants, bars, and dinner shows were added all along the way. It all speaks of a panicked response somewhere in Disney's corporate corridors - call it the Phantom Food Scare of 1971. The evidence is everywhere, except for the evidence of the panic itself.If the numbers aren't compelling - opening nearly twice as many eateries as attractions in a four year span - then perhaps heading back to Disneyland will make the case clearer. Bear Country, opening just six months after Walt Disney World, was the first major addition to Disneyland since The Haunted Mansion in 1969, and existed primarily to add the extremely popular Country Bear Jamboree. Since the Florida version was then regularly commanding a three hour line which could only move every fifteen minutes or so (which means that besides the group in the theater - 350 people - there could be nine additional full theater loads of guests waiting outside and in the lobby, or over 3000 people, or about 15% of the park's total attending crowd), WED built two identical theaters back to back, and placed them in a new area of Disneyland which could accommodate a massive exterior queue. Next to the new attraction Disney placed a massive multilevel restaurant, The Hungry Bear. Even thirty-eight years later it still ranks amongst Disneyland's most massive.

In fact, everything added to Disneyland following the opening of Walt Disney World was built on a scale quite unprecedented in Walt Disney's little family park. Pinocchio Village Haus, if not quite the cavernous dining hall found in Florida, was added to the Anaheim Fantasyland in 1983 and offers seating for several hundred. The entire Flight to the Moon / Mission to Mars attraction was ripped out to make way for a huge new indoor restaurant as part of the ill-fated Tomorrowland expansion of 1998. Today even the intimate Blue Bayou is stuffed to the gills with tables and chairs, far beyond the original intentions.

Clearly Disney's facilities had been severely taxed in the effort to get Walt Disney World open and make it a success, and to paraphrase Sklar, the "surprising demands" from the public touched off a mad scramble to stay ahead. In the process, Disney's methods of evaluating the anticipated level of demand and their idea of scope had altered dramatically.

--

Today in the era of bicoastal Disney passes and special events it's easy to look at the scope of the Magic Kingdom versus the Disneyland original and see something lacking or - perhaps more pointedly - see the start of the sort of thinking that would lead to the massive, monumental open spaces of Tokyo Disneyland and EPCOT Center, and perhaps something strangely impersonal. And although the Magic Kingdom does not lack for quiet, intimate corners, those massive walkways are still dwarfed by later inventions such as Communicore Center or any old walkway between buildings in Tokyo Disneyland. In Florida the scale of the street may be wider, but the scale of the buildings are built to match. Main Street may be twice as wide but the Main Street facades are bigger and taller, and the castle is enormous, costing alone what all of Disneyland cost in 1955.

What we have here then, apparently, is not just a key moment in the operation of the Florida property or even a key turning point in attendance at Walt Disney World but an opportunity to localize at a specific time and place the moment where Disney's theme park design strategy shifted radically, and the key to uncovering this secret history is in the food offerings of the Magic Kingdom. The Magic Kingdom was built up to hold 80,000 people, and EPCOT Center can easily accommodate 120,000. It's easy to spin alternative scenarios from this. Had there not been a massive strain on Disney's resources to keep people fed and happy in 1971, would Tomorrowland have been built in the way it was? Are the massive open spaces in the east and south area of Tomorowland direct descendants of that Thanksgiving day in 1971?

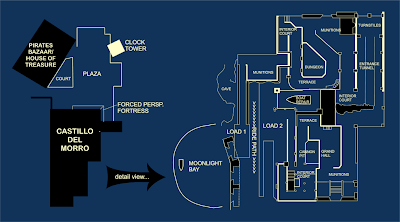

This blueprint of the Magic Kingdom is dated 1971. The finished park followed this blueprint pretty much exactly... except for Tomorrowland. This is the version of Tomorrowland with an Autopia instead of a Grand Prix, a monorail running through it on its way to the Persian Resort, and a Space Mountain contained inside the railroad tracks. Even the railroad tracks followed this blueprint exactly, possibly indicating that as of 1971 Space Mountain was still going to be built inside the plot of land within the Walt Disney World Railroad's "wooden o". So why was it built outside the tracks in 1974? Why did Disney bother to tunnel under the tracks instead of build inside them? Why keep a massive open concrete area when nothing else in the park resembles it? Something changed between 1971 and 1974, and my instinct is that aesthetics was only half of the equation.

There's a famous picture of cars lined up along World Drive waiting to get into the Magic Kingdom on Thanksgiving 1971. Even Disney, ever concerned about protecting their public image of efficiency, talks about that day. If the Magic Kingdom of October 1971 is Disneyland with the "expand button jammed", simply a bigger and fancier copy, then Thanksgiving 1971 is the place and time when Disney's entire approach to the design and construction of their theme parks would change forever. If we follow that herd of cars to their end at the horizon-line, what do we find? I suggest: nowhere real, they point towards the future. Already they're queued up to enter EPCOT. The line forms here.

--

--Reference:

The E Ticket Number 30, Fall 1998 "Imagineering and the Disney Image... an interview with Marty Sklar"

"40,000 Jam Disney Turnstiles; Three-Day ‘Opening’ Under Way" by Jack McDavitt, Dick Marlowe. Orlando Sentinel, October 24, 1971

"Walt Disney's Disneyland" by Martin A. Sklar, 1972

"Walt Disney World Information Guide Compliments of GAF", 1972, 1974, 1975

Walt Disney World News, Vol. 1, No. 1

Walt Disney World News, Vol. 2, No. 7

Walt Disney World Vacationland Summer 1974

"Your Complete Guide to Walt Disney World", 1977, 1978, 1979

(This post is part of the Disney Blog Carnival Number 11. Click to enjoy more Disney blogs and all sorts of other stuff!)