So while the Columbia Harbour House in Liberty Square is an example of Disneys' ability to create compact space which feels totally separate from the outside world of the park in the form of the utilitarian shop or cafeteria, there is another theme design first at Walt Disney World which rejects the traditional wisdom as to what a functional space can be. It's the first immersion queue, the dark and haunting Castillo del Morro at Pirates of the Caribbean.

So while the Columbia Harbour House in Liberty Square is an example of Disneys' ability to create compact space which feels totally separate from the outside world of the park in the form of the utilitarian shop or cafeteria, there is another theme design first at Walt Disney World which rejects the traditional wisdom as to what a functional space can be. It's the first immersion queue, the dark and haunting Castillo del Morro at Pirates of the Caribbean.Some perspective must be used here. We must firstly remember that Caribbean Plaza, which still seems to me to be perfection itself, was an impromptu addition to the Walt Disney World lineup. As such the way it fits perfectly between the Enchanted Tiki Room and Pecos Bill is nothing but a feat of gargantuan brilliance by a team of belabored designers trekking uphill with an absurd timetable and budget lashed to their backs (it is said that Card Walker approved the whole of the area - attraction, shops and taco stand alike - for half of what it cost to build Pirates alone in 1966). Using every trick at their deploy is something of an understatement as to how labyrinthine layout and rhyming structural styles (Spanish colonial becoming Spanish Southwest? A Polynesian temple tower" rhyming" with a Caribbean clock tower? Brilliant!) were combined to turn a very small patch of land into a fully developed extension of its' key attraction. To drive home the enormity of the task one only needs to walk from the exit of Country Bear Jamboree to the far Western end of Pecos Bill and say to yourself "this is how much room you have to build Pirates of the Caribbean."

We must also remember that although we now throw the term "themed queue" around loosely to refer to anything like the experience of transversing the wait areas of Pirates of the Caribbean or Indiana Jones Adventure, that the idea of a themed queue has existed since 1955 - certainly Harper Goff's original Jungle Cruise boathouse qualified as a themed queue, much moreso than those elsewhere in Disneyland. But the innovation of the Castillo del Morro show scene is that it totally dispensed with switchbacks, turning those ropes, poles and chains into solid stone walls. This is the legacy of the design team in this attraction as this is generally our criteria for calling any queue themed or not - do you walk down a big corridor? - and based on this, we must regard latter generation queues, like Indiana Jones, not a progression or refinement - but an aesthetic extrapolation. Castillo del Morro established all the rules.

We must also remember that although we now throw the term "themed queue" around loosely to refer to anything like the experience of transversing the wait areas of Pirates of the Caribbean or Indiana Jones Adventure, that the idea of a themed queue has existed since 1955 - certainly Harper Goff's original Jungle Cruise boathouse qualified as a themed queue, much moreso than those elsewhere in Disneyland. But the innovation of the Castillo del Morro show scene is that it totally dispensed with switchbacks, turning those ropes, poles and chains into solid stone walls. This is the legacy of the design team in this attraction as this is generally our criteria for calling any queue themed or not - do you walk down a big corridor? - and based on this, we must regard latter generation queues, like Indiana Jones, not a progression or refinement - but an aesthetic extrapolation. Castillo del Morro established all the rules.In the process of adapting the ride itself: much was lost, which we can see in hindsight as a crippling blow to the attraction, as much of the effectiveness of the brilliant original was the languorous pace and how slowly and seamlessly three realities seemed to submerge into one.

But this, again, requires some perspective because in 1973 it wasn't yet a proven thing that Pirates of the Caribbean had to be that way: WED was about to build the attraction which proved it. And so the rules were totally changed for the Orlando version. With the removal of the Blue Bayou leg of the attraction, the primary storytelling device which carries the bulk of the time travel conceit, the attraction would be set in the "present" and guests would enter the story just before the still-live Pirates begin their attack.

And so the time travel part of the equation was left up to the structures themselves to carry; just as spectators are swept from British Colonial outposts to Polynesian oasises in Adventureland, they could now be carried away into the romance of the old Caribbean simply by walking a handful of yards. I believe there is an implicit suggestion of time travel in the facade itself, which is as not as much of a significant time slip as the Disneyland versions, but is still significant.

Until recently, you may remember, the facade featured a pirate parrot 'neath the text "PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN" on the north-facing exterior wall who acted as a "barker" for the attraction. Outside a number of tattered, cannon blasted Jolly Roger flags were hung up, and atop the roof, the cannons were still firing. This clearly implicates that the buccaneers have already taken the fortress, a self fulfilling prophecy of the end of the attraction (remember, the only version where the Pirates actually win!). Passing through the entrance arches and towards the entrance of Castillo del Morro is, then, the time travel, resetting the narrative arc and making the journey from end to end of the building the same narrative "closed loop" which the Disneyland version conveys so successfully (and which so validates the form of the attraction itself - since it is a narrative which is closed on either end, we can ride it over and over again and endlessly experience the same events!).

Of course the firing cannons were lost in the 2006 refurbishment due to technical reasons, but they are a key element in the interior logic of the space and we must keep them in mind. In 2007 the Jolly Roger was replaced with a Spanish flag, which better suits the "there is no time travel" story Caribbean Plaza tells and completes the removal of the subtle element of time travel I have outlined above which was the net result of the removal of the Barker Bird parrot at the entrance.

And now, a more specific breakdown of elements of the first immersion queue.

1. Simulated Nightfall

Disneyland's Pirates entranceway has gotten a lot of flack since the opening of the version in question, despite the fact that it is a brilliant visual thesis statement on the entire formal mode of the attraction's disjunctions of space and time. But let it be said that one of the things Disneyland's Pirates accomplishes in its' entryway is a precise simulated sunset, where spectators are pushed farther and farther away from the bright California sunlight and emerge into the nighttime bayou. Since the essential aesthetic mode of Pirates of the Caribbean is unchanged at Walt Disney World, Castillo del Morro does this same feat in a much larger but still brilliant space, the extended plaza in front of the attraction entrance which gradually dims the sunlight, replacing its' bright glow with the simulated skylights casting false sunlight, which will again transform into the dim glow of incandescent lights and, finally, firelight.

Alongside this space is a "hidden" courtyard which used to spill vacationers out of the House of Treasure giftshop with its' own little forced perspective upper balconies - the most effective in Caribbean Plaza due to the extreme angle the courtyard forces you to look up at them, really tricking your sense of scale. This courtyard, and the one across the way between the old Princessa de Cristal and Golden Galleon gift shops, really are as good as anything New Orleans Square can offer. WED really learned from Herb Ryman's "pocket" concept - if there's vacant space between establishments in your area just make them out of the way transitional areas rather than yet more break rooms or offices. A well placed, quiet courtyard is worth a million of the more traditional false portals in expanding a limited space into infinity, creating a "stratified" visual experience.

But calling the court hidden is a kind of misnomer, because you're meant to see it, to look at it, even casually glance at it as you march onwards into the dark fortress. It is a setup, saying to the spectator in no uncertain terms, that space is tricky, that you will be expected to look not at one space but all those which abut it to get the full experience of the attraction. As a pocket, as a portal, and as a thesis statement about the attraction which it prefaces, the Castillo del Morro plaza is as key a movement towards the ultimate goal of the attraction as can be imagined.

2. Layout and Design

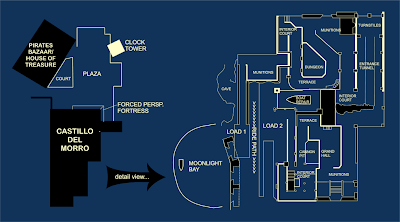

Once inside, the complexities of design really begin to pile up, so let us first preface this section with a bit of perspective on scale; please click below to expand a diagram.

As the scale diagram shows, the Pirates entrance plaza and facade does not take up significantly more space than the queue and double load area. Thus, there will be a dramatic narrowing of the potential for movement once the guest enters the Castillo proper. One way that the fortress queue feels massive, indeed endless, is how tightly the corridors and rooms twist around each other, yet none is visible from the other, giving a sense of progress but an extreme sense of misdirection. The tactile sensation of being lost is conveyed fully through having the spectator constantly navigate sharp turns and hairpins, but failing to make significant progress in covering ground.

This is why the queue for Indiana Jones Adventure is a very different kind of experience, because you endlessly are allowed to move forward, always moving towards the destination. Here, you feel as if you may have gotten yourself in trouble.

Increasing the sense of disorientation is the use of ramps. The Entrance Tunnel which leads to the first of three "inside outside" interior courtyards slopes up dramatically and is heavily crammed with arches, effectively restricting the spectators' view of the top of the ramp from the bottom of it. From here the queue splits into two different sides; one which will proceed through the military side of the fortification, with dungeons and cannon nests, a

nd the second which will proceed through the side of the fortress the soldiers would likely have inhabited, with a banquet hall, peaceful interior courtyard, fountain, and gunpowder pit. While the inhabited portion of the queue remains level (increasing the sense that it is used for living space), only sloping down at the very end to bring guests down to the load point, the Dungeon side is trickier.

nd the second which will proceed through the side of the fortress the soldiers would likely have inhabited, with a banquet hall, peaceful interior courtyard, fountain, and gunpowder pit. While the inhabited portion of the queue remains level (increasing the sense that it is used for living space), only sloping down at the very end to bring guests down to the load point, the Dungeon side is trickier.Once the top of the entrance ramp is reached, the queue immediately and dramatically slopes down to ground level again. This is done to reinforce the idea that guests are descending into a lower area of the fortress, although no net elevation change has actually been achieved! Since walls and doors block out any frame of reference for the actual height of the area, subconsciously the brain has been prepared to accept that it is now in a lower area of the fortress.

Then, the ground begins to ascend again, because guests are approaching the original, famous Chess scene, Marc Davis' brilliant gag of two skeletons forever locked in check in the dungeon. This being Florida, only so much space can be dug into the ground to give a proper dungeon, and so once again the floor rises to take advantage of what little vertical space can be exploited in the (already elevated!) queue.

At this point the ramps have brought us from ground level to a second level, then back to ground level, then back to the second level, all while convincing the brain that it is deep underground at this point. The rest of the queue on the Dungeon side is an ascent to a third, top level so that the boats can pass underneath the queue, then a quick slope back down to a ground level load area.

At this point the ramps have brought us from ground level to a second level, then back to ground level, then back to the second level, all while convincing the brain that it is deep underground at this point. The rest of the queue on the Dungeon side is an ascent to a third, top level so that the boats can pass underneath the queue, then a quick slope back down to a ground level load area.There are a number of fascinating repetitions of scenes and visual cues throughout: for example, although the Inhabited part of the fortress is replete with locked racks of guns and swords, it does not feel as imposing as the Defense part of the fortress, which features tall, vaulted ceilings and rough hewn rock, not the plastered walls of the soldier's side.

Both feature interior courtyard scenes, but while the Defense side of the queue is an ascent to a gun nest overlooking the load point and a ship under repair, the Soldier side is a beautiful courtyard with a staircase and a trickling fountain with a forced perspective scene above of a nighttime alcove with hanging plants. Both feature a music track of a lonely musician strumming his guitar, appearing in this peaceful little courtyard to suggest a bored night watchman. It appears in the Defense side emanating from one of the cells which rings the Chess scene, suggesting a prisoner spending his final days alone in the dungeon. Identical music, two diametrically opposed effects.

3. Plot and Effect

For two complimentary sides of the same coin, each side of the queue has a totally different effect on the audience. In the Soliders' side of the Castillo, with its' signs of abandoned inhabitation everywhere, a feeling of loneliness takes effect. It is a long, lonely, confusing trek.

The Defense side however, with its' subconscious effects of going underground, the side which is placed nearest those firing cannons on the roof, the side meant to withstand an invasion, is scary. Both queues wrap around a little box of a room which features some supplies for the fort, in which is placed a speaker which plays the sounds of the Spanish preparing for an attack interspersed with a recording of the attraction's signature song "A Pirate's Life For Me". When the song plays it echoes down through those corridors just right to make you believe that the Pirates of the Caribbean could be around any of those innumerable blind corners, itself a brilliant setup for the attraction itself. But it is scary, and the skeleton imagery featured on the Dungeon side drives home the fact.

But both sides, with their stone walls, barrels of gunpowder, rifles and cannons are replete with constant reminders of impending violence, that the Pirates are indeed coming. Rather than the lively fortress the exterior gun battle and bright Plaza prepares us for, we get signs of inhabitants who have all suddenly run off somewhere, leaving behind only a night watchman and the dead and dying in the prison. In creates a tension between our desire to see the titular pirates and our apprehension at actually unexpectedly encountering them, which crystallizes in the load area, where we pass a torchlit cave and hear Pirates burying treasure, and our apprehension again deferred. As the boats scoot out of the load area and into the cavern they pass the open water and we see for the first time the reason we have been so strangely alone: there's the pirate ship out in the harbor, the pirate ship we'll encounter again in just a few minutes.

All of this is a significant reconstruction of the same narrative paces of the Disneyland version of the attraction by the original design team, so much so that although on the terms of its' predecessor it is not really a success, on its' own terms - the terms that really matter to the interior life of the attraction - it is a more radical reconstruction of Pirates of the Caribbean attraction than the later generation, much lauded Paris version.

What the Castillo del Morro queue is, is that it is a chronicle of the town which the pirates invade, an elaborate half-narrative setup through which we must pass in order to see the rest of the story. In this way it is arguable that the Plaza and Queue of Pirates Orlando is an admissible attempt to shift the storytelling techniques of the Anaheim Queue and Blue Bayou into practical space, which is a pretty brilliant way to do the same thing as the original on very little of the budget of the same. That the Castillo del Morro queue arose out of practical necessity is inarguable, but it changed the rules of the game forever and as such it must be considered the great queue, the original that was the enabler of one of WDI's most interesting narrative tools.