December 22, 1972 - The Magic of Walt Disney World

This film was released bundled with Snowball Express, for those who want to recreate the experience at home.

Promoting the theme parks with documentaries is an old idea, going back to at least 1954, but the two Disney theme park theatrical films are really in a class of their own. Relatively widely known today is the terrific 1956 Disneyland USA, thanks to a pristine transfer for DVD in 2008. The 1956 film is great and invaluable, but the one I'd do unspeakable things for a perfect copy of is the 1972 Magic of Walt Disney World. It's the Citizen Kane of theme park promotional films.

For longtime fans of the Florida property, the opening of the film is almost unbearably poignant. Narrated by Steve Forrest in what is bizarrely enough his final Disney gig, as Buddy Baker's melancholy "Walt Disney World" theme rises and the camera soars over a brand new Cinderella Castle, it's impossible to not get a little choked up.

Compared directly to the Disneyland we see in Disneyland USA, which is often unrecognizable, The Magic Kingdom has changed comparatively little since 1972. Things are missing all around - no Tomorrowland, no Pirates, no mountain range - but even a casual visitor would readily identify the bulk of the park. As a result, Magic of WDW has something Disneyland USA doesn't quite rise to, which is nostalgia. It may be because the early years of Disneyland today seem so alien and remote, a park a bit closer in tone and execution to something like Pacific Ocean Park than the space-age wonderland it became. Disneyland USA is consistently mind boggling and through, but it doesn't quite make the leap to lived experience that you get in Magic of WDW.

If you watch enough theme park promotional film of the era, eventually you get to where you've seen all of the same shots over and over. The same basic footage found in From The Pirates of the Caribbean To The World of Tomorrow or Disneyland Showtime ended up being used over and over until well into the late 80s. If you're a fan of theme parks this means you spend a lot of time seeing the same stuff. The film which this is ostensibly the companion piece to is The Magic of Disneyland, a 1968 16mm compilation of all of the best shots of Disneyland in the Disney film library. The Magic of Disneyland is terrific, but for seasoned fans, it's also all literally been seen before.

The Magic of WDW greatly benefits from being entirely new footage and also benefits from being obligated to cover a wider scope of material in a limited amount of time. The attractions which receive the most luxurious coverage are The Hall of Presidents, Country Bear Jamboree, Mickey Mouse Revue, and Jungle Cruise, where not a single reused shot from Disneyland may be found. By leapfrogging over something like Haunted Mansion, the film is able to spend its time highlighting the recreation and lagoons which have always been Walt Disney World's secret weapons - the shots of the sunlight sinking below Fort Wilderness or a sidewheeler steaming across a dusky Bay Lake are extremely powerful evocations.

The distinctions between what's a great sell and merely a good one are hard to delineate. Perhaps ultimately the most marvelous thing about The Magic of WDW is what's not there as much as what is. With wide, circling shots of the park, the barren Tomorrowland, the empty Frontierland, the dead-end Adventureland are all on full display. The park we see here is similar enough to be affecting but different enough to be novel.

Disney made other terrific promotional films - there's A Dream Called Walt Disney World, from 1981, and A Day at Disneyland, the early 90s in-park souvenir video. A personal favorite of mine is Disneyland Fun, a Sing-Along VHS that has enough of a following to have attracted a DVD release. But for my money none of them quite touch The Magic of Walt Disney World for the indefinable quality that brings viewers there. And it does it all without a single appearance by a Disney character squawking into the camera.

December 22, 1972 - Snowball Express

We've reached a milestone here with Snowball Express: this is the final Dean Jones film in our series, and with the conclusion of this entry we have watched the bulk of his career at Disney.

There's two films he made for Disney before the death of Walt - That Darn Cat and The Ugly Dachshund - and he'll return in a few more years for two more dips into the well, with The Shaggy D.A. and Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo. In both of those films, Dean is a sort of second banana to another Disney star - a fairly convincing older Kirk Cameron in D.A. and yet another spin as the third ring in a circus dominated by a crazy mechanic and prop vehicle. As a result, it's fair to say that we've seen the section of Jones' career which fixed him in memory as a representative of the era at Disney. With Snowball Express, he passes that honor onto Don Knotts.

Yet looking at the world of performances in Disney films, it's both a better and more diverse field than you may suspect. Take Steve Forrest, who for a few years seems to have been groomed to be a Disney star in the vein of Fred MacMurray - the Classic Dad. He's excellent in Rascal and fine in The Wild Country, But that's where the trail ends before Forrest goes back to TV work. Then there's David Tomlinson, the "secret weapon" packed into Mary Poppins and Bedknobs and Broomsticks. Other actors did similarly excellent work in less distinguished movies - Brian Keith is terrific in Scandalous John, but that film was a flop and is rarely seen today. And of course Kurt Russell is terrific in everything he's in but we think of Russell's career as a bigger thing than just Disney whereas Dean Jones is thought of exclusively for his time at the Mouse House.

Make no mistake: if this blog series had a mascot, it would be Dean Jones. So what makes him the definitive Disney actor of the era?

Well, for one, I've found that these Disney films tend to rise or fall on a strong leading actor and a sense of some kind of atmosphere. Jones was, strictly speaking, reliable. I feel that calling him "reliable" is almost an insult in light of the work he did in impossible situations: how many other actors could realistically have a reconciliation with a car? Watch the other Herbie movies: plenty of other actors failed where Jones succeeded.

So we can also say that Dean was reliable in ways that were complimentary to the kind of movies Disney made but probably seemed an unmarketable skill set in other studios.

And, Jones had some range. Not a lot, but the movies he starred in didn't require much. He could be dramatic on cue, evoke sentiment, and quietly carry the story with dignity. The actor Jones most often reminds me of is Jimmy Stewart, especially in his younger years. Not a performer of incredible range, with the right material and director Stewart could be incredibly effective, even scary. Jones has a similar physical build, a similar common-guy persona, and a similar skill set.

In that vein, Snowball Express may be the best use of his talents of them all. With no talking dogs, cars, or invisible pirates to distract, Jones carries the entire film, and he does it very well. Paired again with the master of lackadaisical wide shots Norman Tokar and producer Ron Miller, who inexplicably were allowed to continue making films after the abominable Boatniks, Snowball Express is fondly remembered for good reason - it's the most watchable and enjoyable Disney comedy of its era.

A ten minute prologue which begins with a defeated Dean Jones as another Man in the Grey Flannel Suit surrogate and ends with Jones stalking towards the camera shouting "Silver Hill, Colorado!" shows Jones receiving an inheritance and saying goodbye to his hated desk job in a way most of us dream we could. His "Grand imperial Hotel" turns out to be a rambling dump, but he's determined to turn it into a ski resort - against all odds.

That almost everything in Snowball Express works is a surprise. Perhaps enervated by the unusual climate and location, Tokar and cinematographer Frank Phillips create an endless winter, the snowdrifts visually offset by the decaying Hotel Imperial in a way which, bizarrely, puts me in mind of Doctor Zhivago. The art department really went to town on the decaying Hotel Imperial, and that hotel has more atmosphere than the last three Disney movies put together. Johnny Whitaker, who spent most of last week proving that he cannot carry a film alone, provides a perfect comic foil for Jones and his wife Nancy Olson. Harry Morgan is nearly unrecognizable as a washed out drunk living in the barn behind the house. Even the resolution is somewhat surprising - the film allows Jones to lose, over and over, even when we're positive he's about to succeed, only to demonstrate that he's already won.

Snowball Express is a difficult film to write about. It works well, but it's hard to describe any comedy with little on its mind besides good natured jokes without stepping on the jokes by describing them. What can be said is that Snowball is literally the product of plugging together every component that ever worked in another Disney movie into one film. There's an unexpected windfall (Million Dollar Duck) of a property inheritance (Monkeys Go Home), computer antics a'la Dexter Riley, a beleaguered but determined father (Absent Minded Professor), a sassy son (take your pick), a climatic race (The Love Bug), and the grizzled sidekick who saves the day (Blackbeard's Ghost). It shouldn't work at all, it should feel like desperate tire spinning like Million Dollar Duck does, but the unusual location, snappy editing, a funny script, and Dean Jones all conspire to pull it off.

If anything the comparative excellence of Snowball demonstrates that Disney already had all of the elements of a successful version of that one movie they kept making laid out in front of them and for one reason or another failed to capitalize on the constituent parts. Snowball Express makes it all look easy. Along with Now You See Him, Now You Don't it's the most successful and purely enjoyable "Disney Live Action Comedy" of its era.

February 14, 1973 - The World's Greatest Athlete

Comedy is a fickle thing. For every W.C. Fields, Marx Brothers, Buster Keaton, or Jerry Lewis, there's a whole herd of comedians waiting in the wings to whom time has not been as kind to. Some are forgotten but still talented, but a great deal have simply been rendered obsolete by social change and taste. A relic like The General may be one of the few silent films of its era to command audience attention, admiration, and money today, but in 1927 it was a bomb. The comedy that beat it at the box office? Hands Up!, a forgotten (and lost) western, roundly praised in tones much more glowing than those afforded Keaton's masterpiece.

I'm saying all of this in the earnest hope that at one point in time, The World's Greatest Athlete was at least... funny. That may be needlessly optimistic. The New York Times wrote of it in 1973 as it inexplicably played at the Radio City Music Hall: "It should be stressed, however, that this ribbing of the Tarzan myth runs a good, clean course that should grab all red-blooded sports fans up to and including the 14-year-old group. It might be added that everyone from coach Amos to Jan-Michael Vincent, in the title role, athletically tries without much success to make all this good-natured nonsense funny."

The World's Greatrst Athelete stars John Amos as a beleaguered college coach on the ropes with his employers who discovers a (white) Tarzan surrogate during a safari to Africa which mostly involves Amos and his irritating henchman Tim Conway standing in front of process screens. If nothing else, it's momentarily heartening to see Amos as the comedy star of a Disney film. Black actors in Disney films prior to this moment appeared in roles ranging from invisible to demeaning, with the exception of James Baskett in Song of the South, and the years between the release of that film and our own time has made appreciating his performance very difficult. Amos' race isn't even a peripheral concern in Greatest Athelete - it only seems to be there to get Amos to Africa where he can discover Nanu, the athletic jungle boy who runs faster than a cheetah. Whatever good will is generated by Amos, however, quickly dissipates as the film introduces an African Witch Doctor, played by Roscoe Browne, in full cartoon mode.

Athlete unspools for a soul-deadening 93 minutes through every expected stock plot situation. The only surprise comes at the one hour point when the Witch Doctor Gazenga shrinks Tim Conway, for no reason whatever, to three inches tall. Conway stumbles around through unfunny situations in impressive "giant size" sets, in a complication that seems to have been invented to get an extra ten minutes into the run time. I laughed at all of this exactly once - in a gag where Conway tries to "muscle into" the frame during a TV interview with Amos, and even that joke was repeated again - and again - and again - grinding what was the only funny, spontaneous moment of the film into submission.

About halfway through this most supremely unfunny of comedies I began to get an alarming feeling that all of this was starting to feel familiar - the endless panning shots, the endless zoom shots, and the endless panning shots that end as zoom shots were too much like something I had seen before.

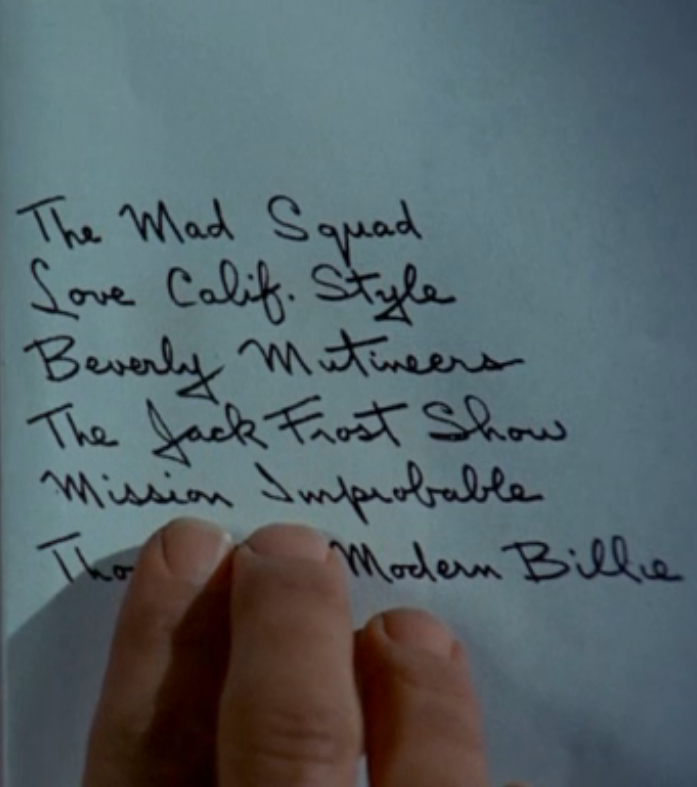

A quick check on IMDb proved me to be correct - Robert Scheerer also directed the inane, endless Grand Opening of Walt Disney World TV special, a 90 minute extravaganza that reportedly sent Roy O. Disney into a rage. Badly, quickly shot in a Magic Kingdom still under construction and punctuated with lousy wide shots and crash zooms, The World's Greatest Athlete is just what you're looking for if you want more of the comedy stylings from the team behind this:

|

| "Life is a kumquat!" "What?" "As somebody said?" |

|

| "Come on , Herbie!" |

I'd like to point out in 1966, Disney changed their plans to feature Louis Armstrong as King Louie in Jungle Book for fear of causing offense by casting a black man as a monkey. This same company made a movie in 1973 where an African Witch Doctor stops a photo shoot to place a bone in his nose. Progress?????

Comedy may be hard, but watching The World's Greatest Athlete is even harder. It features not one funny joke, one amusing scene, or one likable character. It's embarrassing to see Disney trading on the goodwill generated by their name to be passing stuff like this off on the general public.

March 23, 1973 - Charley and the Angel

One of my favorite movie stories: in the early 80s, a young director named Robert Zemeckis had a script for a lighthearted fantasy comedy script he was shopping around town. Every studio turned him down; in the early 80s in the wake of Animal House, the only comedies studios were interested in making were raunchy sex comedies. "Take it to Disney!", every studio suggested. Out of options, Zemeckis took the movie to Disney. Card Walker flipped out. "Are you crazy? You've got this scene with the guy and his mother in the car -- this is incest! We can't make this movie!"

That script was called Back to the Future.

At a certain point from the 60s onward, as movie studios raced to stay ahead of social trends, Disney was the only studio in town for a certain kind of movie. The early 70s was the era of disaster movies, The Godfather, and The Sting. The Exorcist was causing what can be mildly described as mass hysteria in theaters. The highest grossing comedy around was Blazing Saddles. Nothing the rest of the motion picture industry was doing was remotely compatible with Disney's simple comedies.

So for a script like Charley and the Angel to have a shot at getting made it really had to be a Disney movie. As far as Disney movies from the early seventies go, it's a good one, and it dominated the box office throughout Easter 1973. Still, being a Disney film comes with come conditions and Disney sometimes giveth as much as it taketh away. Charley & the Angel compactly demonstrates the upsides and downsides of being Disney in 1973.

Set in the Great Depression at the tail end of Prohibition, Charley features an alarmingly hoarse sounding Fred MacMurray as an uptight hardware store owner who's visited by an angel played by Harry Morgan sent from heaven to deliver his final judgement. Heaven, however, can't quite make up its mind how and when it will do Charley in, and in true Hollywood tradition the imminent end of his life gets Charley to thinking about all the things he wishes he'd done....

You've probably seen one of these movies before, but what you probably don't know is that they have an official name: film blanc, derived from the better known film noir. Both styles emerged from the golden age of Hollywood and both styles deal with folly and mortality, but while film noir is all deceit and annihilation, film blanc is about transcendence, ennobling the human spirit in its darkest moments.

The most famous film blanc of all, and the film Charley & the Angel most resembles, is It's a Wonderful Life, but there are many others. There's the well-remembered Topper and Topper Returns, as well as Blithe Spirit, representing one common variation on the theme that protecting angels are ghosts. Others play on a Faust variation, such as the charming but non-PC Cabin in the Sky, while others such as Peter Ibbetson play on darker themes. Morality is a common thread: Ernst Lubitsch's Heaven Can Wait beautifully redeems a kind-hearted playboy but makes no judgement on his sexual profligacy.

One reoccurring theme in Film Blanc is heaven-as-bureaucracy. In Fritz Lang's film Liliom from 1934, Charles Boyer ascends to heaven past mechanical-looking angels after committing suicide and finds himself in a celestial duplicate of the Paris police stations he'd haunted in life - down to the same old guy behind the desk with the same defective stamp. Maybe the grand daddy of all films blanc is Powell and Pressburger's over-the-top A Matter of Life and Death, where heaven is some weird black and white stentorian Tomorrowland observatory looking out over a Technicolor world.

There's a bit of this left over in Charley. Charley's angel reports secondhand confusion in heaven as Charley continually avoids heaven's fatal blows, the official decision on his doom, is, as they say, mired in delays. This is exactly the sort of uncertainty films blanc often play with - as the creepy, Nosferatu-like angels in Liliom say, it would be too easy if death were the end of everything.

Not to detract from MacMurray, but Harry Morgan as the angel is nearly the whole show here. Morgan delivers his lines in an amusing clipped dialect that I suppose is intended to recall the era he hails from - the turn of the 20th century. He occasionally offers insight into the afterlife of an angel - he only vaguely recalls his life on earth - and gets into some amusing hi jinx with roller skates. Occasionally only his iconic hat, cane and gloves materialize, briefly turning the film into an Invisible Man movie.

The film gets into murky water the Disney studio is ill-suited to traverse in the final third, when Charley's young boys are encouraged to get jobs and end up running liquor to a speakeasy. The operation is overseen by Richard Bakalyn, who by now has become Disney shorthand for "=gangster". Then the Big Boss unexpectedly arrives to take over the operation and a harebrained car chase ensues, introducing a horrible Vito Corleone impersonation and deflating the easygoing mood.

This is what I mean when I say that Charley & the Angel represents the benefits and drawbacks of Disney in 1973. No other studio would touch a film like this, but Disney is repeatedly stuffing things into Charley just because, well, it's what they do. There's a gangster because, um, it's a Disney movie. There's a lame car chase because, um, it's a Disney movie. One reason why films blanc have found and retained a loyal fan base is because the supernatural subject and heavy atmosphere often bring out the best in film art. The movies aren't just uplifting and lighthearted; the subject matter nearly demands cinematic audacity.

Compared to even a studio sausages like Cabin in the Sky or Peter Ibbetson, Charley is remarkably tamped-down. While it never affects the film badly from the perspective of a Disney film, as a film fan I was disappointed to see promising material end up so predictable. As it stands it's a rare dramatically successful film from this studio in this era, but with a bit more dramatic weight and a director unburdened from the need to make a film of a certain look and house style, Charley could have been exceptional.

The film is based on a book called The Golden Evenings of Summer, which I've looked for details about online, and the book seems to be a Dandelion Wine-style nostalgic reverie with no angels of any kind. If this is true, then Disney deserves credit for building a film up around it that plays well to their strengths just as quickly as we point out their weaknesses. Charley's main pleasures may be atmosphere instead of incident, but it's a fairly pleasant way to spend your evening.

The Final Week of The Age of Not Believing will be coming soon. The films are One Little Indian and Robin Hood.