Note to researchers: this post has basically 90% accurate information but does not present the full version of this attraction's story - please tread carefully until such a time as I can update this series!

If you are a theme park fan you have almost certainly at one point or another heard about the aborted 1971 attraction Western River Expedition. Western River is largely considered the greatest (or second greatest) unbuilt theme park attraction ever, but just as interesting as the attraction is the legend behind it: an earnest, serious effort to outdo the 1967 Pirates of the Caribbean, Western River Expedition was an ambitious attraction done in by just the right combination of bad luck, timing, expense, and its creator, Marc Davis. It's a great story, and a great myth, about a great designer and his best effort.

Until 2011, Western River was largely a "great whatsit" to me. We had all read the stories and seen the art, but it never seemed like an attraction that could actually cohere into actual reality - there were too many things in these tellings that made too little sense. Then, I was given the opportunity to spot-check a number of video presentations ultimately destined for D23's "Destination D" event, one of which was a partial virtual rebuild of Western River Expedition, I finally saw a number of models and made a number of connections that finally made sense of a ride that seemed previously to make very little. Building on the revelations I experienced while trying to mentally order the ride for the video, I'm now able to offer what I think is the most complete and accurate overview of the attraction yet possible.

The first thing which must be said is that besides getting the essential order of many things wrong, many of the online retellings of this ride have done a disservice to Marc Davis by continuing to reprint artwork for scenes that were not included in the final ride. Marc was a brilliant illustrator, and he produced mountains of artwork to demonstrate his ideas, but only a fraction of these were ever seriously earmarked to go in the final product.

Imagine, for example, if Haunted Mansion had never pulled itself out of development hell and we just happened to have lots of pieces of artwork floating around like this:

This would give a false impression of what the whole experience was truly intended to be. That's sort of what happened to Western River Expedition. In my digital tour in this article, you'll see that Western River was not only sensible, but dramatically very well constructed and very soundly conceived. But I'm getting ahead of myself. Let's get oriented by going myth busting.

I. THUNDER MESA TRUE AND FALSE

Thunder Mesa and Western River Expedition are the same thing.

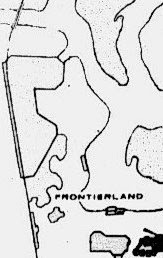

False. Thunder Mesa was a network of attractions surrounding a very large show building, inside of which was the Western River Expedition. Besides the Marc Davis attraction inside, Thunder Mesa would've offered a runaway mine train, a canoe flume ride, and walking trails and exhibits. It was to be situated on a piece of land carved out just for it in north-western Frontierland.

Western River Expedition was intended to be a twenty minute long attraction.

False. One of the reasons Western River had such a huge show building was because the whole idea was to recreate the vast open desert plains indoors. The ride would've been several minutes longer than the Florida Pirates of the Caribbean but not quite so long as the California Pirates of the Caribbean; probably ten to twelve minutes. This was not an unreasonably scaled project.

In the attraction load area, the Walt Disney World Railroad would have looked down from above.

False. The Railroad did indeed peek into the ride, but not at the point commonly described.

The ride would've had more audio-animatronics than any ride ever.

True and false. WRE was expected to have slightly more figures than Pirates of the Caribbean, but not nearly as many as World of Motion ended up having in 1982. I know it's hard to think in relative terms about some of these things, but cost of figure production alone was not was sunk Western River.

Western River Expedition would've ended in a large, outdoor drop, making it redundant with Splash Mountain.

False. I'm not sure where this idea began, although I will show how it occurred. Western River Expedition itself was, like Pirates and Small World, entirely contained inside its own attraction show building and never would've gone outside. Thunder Mesa was slated to include a canoe-themed log flume which would've climaxed in a long, rapid descent thru outdoor rapids down the front of the mesa. This ride was being developed separately from Marc Davis' interior show, but at some point somebody conflated the two.

Hoot Gibson, an audio-animatronic owl, would have narrated Western River Expedition.

Probably false. There are no pieces of Marc Davis art of Hoot, nor does there seem to be any places in the attraction where he could completely comfortably fit. When Mike Lee interviewed Marc Davis in 1999, he asked specifically about Hoot Gibson and Marc had nothing to say about him.

Of course, there's plenty of stuff in rides like the Haunted Mansion that no real concept art exists of, so that doesn't prove much. What I think is more likely is that Hoot was going to be featured in revised versions of the attraction that Marc was preparing following the opening of Walt Disney World. Since we can't be totally sure of that, these articles attempt to present the version of the attraction which came the nearest to actual realization: the original, 1971 version.

Wasn't the ride revised to make it more "politically correct?"

True. As documented by Mike Lee, at some point Davis prepared a version of the attraction which removed the Native American component all together, instead expanding the showcase "Saturday Night On The Town" sequence to fill the gap. Changing attitudes in America through the 1960s and 1970s would have made the use of native tribes for comedy purposes fairly objectionable, even if I'm not sure that Disney would have been able to attempt a Pirates of the Caribbean-style "purge"as they did in the 1990s. Unlike some, however, I'm not sure that this is what killed off the project, although it inarguably did cause the project to spin its wheels for years.

Western River Expedition never happened because the ride was conceived on an impossible scale.

False. If I had to choose a single thing that killed Western River Expedition permanently and forever, it's because Disney didn't want to be in the business of making rides like this past a certain point.

Following the Energy crisis, Walt Disney World went into full-on money conservation mode, only proceeding with Space Mountain because the ride foundations were up prior to the gas shortage. Throughout 1975 and 1976 the Magic Kingdom and Disneyland were stuffed to capacity due to the popular Bicentennial promotion, and at the end of 1976 WDP announced their intention to move forward with Tokyo Disneyland and EPCOT Center, two projects that monopolized all of their resources for six years.

Marc Davis retired in 1977, and so Western River Expedition was without its core advocate. The timing was simply all wrong to get it built.

But over the years because it was pretty elaborate and never got off the ground rumors have spread that Western River was just too big to come true, which is nonsense. Choose any of the 1982 Future World classics and you have an equally elaborate attraction. Western River was built on a foundation of what Davis knew Disney could do well: rocks, lighting, special effects and a slow moving boat.

If there's any one thing I want readers to come away from this article with, it's the fact that Western River was not some crazily impossible thing. Davis always built his designs and ideas around what he knew the technological limitations of WED were. It not only was possible in 1971, but it's still possible and compelling today.

Now that I can break down the attraction into a full picture of what was intended, I hope that a lot of misunderstanding can finally be erased. So let's go into our first section, and describe Thunder Mesa in some detail.

II. THUNDER MESA: THE EXTERIOR ATTRACTIONS

We've all seen this picture:

Most of you have probably seen this image dozens of times online and blown it off as totally impossible to comprehend, and that's because nobody's ever gone out and shown exactly how each part fits together. So let's start by doing that.

On certain early Magic Kingdom blueprints which make a frequent appearance online, the foundation of the actual Thunder Mesa complex may be observed, like so:

What you're being shown here is strictly a foundation; moreover, strictly a foundation for the interior attraction. The disconnect between the concept art and the final product is very apparent. There's two additional resources to help paint this picture for you; a model and a lineart drawing.

Take another close look at that postcard we've all seen; now, here's what Thunder Mesa looked like... from above:

And here's a gorgeous lineart piece from a slightly different viewpoint:

Okay, now that we've got these in front of us, let's start picking out landmarks we can recognize. There's three major landmarks on the outside of Thunder Mesa. The first is this curious collection of buildings on the southernmost side:

Notice the train running through the center of it. This was supposed to be the "Mesa Terrace", a sort of Western version of the Blue Bayou. The lobby and tables would be housed in the buildings running along the walkway, by all appearances a normal Western town from the front but inside a single connected curved open space. Inside, under the roofs of the town, tables faced out across a bucolic old west town, complete with a forced perspective central "street".

Every so often trains would roll through, carrying passengers up towards the pleateu of Thunder Mesa. In terms of style and execution, I imagine this as being something like a cross between the Blue Bayou and the boarding area of Disneyland's Mine Train Thru Nature's Wonderland:

|

| Gorillas Don't Blog |

A bit further along, a rambling railroad platform sits by a cove that's fed by a gigantic waterfall tumbling down off the top of the Mesa and flowing back into the Rivers of America:

This structure provides the loading and unloading platforms for two attractions, both of which take riders up into the top of the Mesa: a runaway train ride and a flume ride styled after white water canoeing.

Both attractions would bring riders to different areas of the top of the mountain, these areas probably being very much like various tableau and scenes seen along Nature's Wonderland.

Look carefully here and you can see a forest of cacti on the left, probably not dissimilar to Nature's Wonderland's Saguaro Forest. In the center is a Painted Desert, a forced perspective hill that rises up to a vanishing point above a tree line, thus implying that it continues on forever. To give an idea of how this would have worked, until the late 1980s the Walt Disney World Jungle Cruise used the same visual trick on their African Veldt:

On the right we can see a sort of "geyser gulch" the runaway train travels through just before it makes the big trip back down off the Mesa. Across the entire top of paths and trails. The kinship with Nature's Wonderland has no doubt fueled the rumor that Pack Mules were intended to go up the top of Thunder Mesa, but I've found no real suggestion of this in reality and the model we have suggests to me that these were walking paths.

As for the canoes, they would have loaded at a platform just below the train along that sheltered Western cove, then proceeded into a cave in the front of the Mesa, moving through a new version of the Rainbow Caverns as they chug up a lift hill:

Arriving at the top of the Mesa, the canoes would have commanding views of Frontierland and Adventureland, slip down through the valley of saguaros, then began a rapid plunge down a long canyon river, ending in some thrilling white-water rapids before returning to Load:

As it turns out this attraction was among the first assignments for a young George McGinnis, so as crazy as all of this stuff seems there were indeed teams moving forward with these ideas.

Now that we've identified the major components of Thunder Mesa, let's color them in on that pencil overview. The entrance and (possible) exit to the Western River Expedition appear in orange, the canoe ride path in blue, and the runaway train track in red.

Oh, and those pueblo houses, so famous for appearing on the postcard and the 1971 room wall map? Pretty sure those were just for decoration, so sorry guys, no Indian dance circle like Disneyland had.

|

| Sorry, pueblo enthusiasts! |

It's also easy to see how the boat ride inside the mountain and the canoe ride outside got conflated, leading to the idea that the Marc Davis boat ride ended with a large, outdoor drop a'la Splash Mountain. Thunder Mesa's white water course would have been a totally different kind of thrill than Splash Mountain's straight-down final plunge, but the similarities are there.

It's also hard not to see how Big Thunder Mountain is actually a pretty good compromise for the train and canoe ride. The unique idea of having two different rides which move through different areas of the Mesa is a great one, and that Mesa Cafe with its pastoral outdoor old west town seems to me a huge loss. But that was going to be Thunder Mesa, everyone. That was it.

III. WERE THEY ACTUALLY GOING TO BUILD THIS THING?

Apparently, yes they were. Multiple models were worked up, and I'm told blueprints and schemata were prepared by MAPO. There's even the old story that figure manufacture had begun. This wasn't a pipe dream, it was a buildable concept that Disney was ready to start work on.

They built the attraction's accompanying Train Station in 1972. Had the attraction been built, this structure would have sat near the colorful facades of the Mesa Cafe, and shortly after steaming out of the Frontierland station, the trains would have passed into a cavern in the side of the Mesa.

I've used the model and art above to give a conception of the scope of Thunder Mesa because, remarkably, they all match. There are, however, a few discrepancies. There's this 1969 elevation by Mitsu Natsume:

This thing doesn't square with either the 1970 postcard or the model or line art, so I suspect it's an earlier version of the project. Expand this one, please, and notice that the area where the entrance to the boat ride was to be has been pasted over with an ore elevator without an entrance below it; I suspect this has been modified at some point to be passed off as Big Thunder Mountain concept art.

And then there's the big Magic Kingdom model prepared in 1969. This model has some interesting discrepancies with the park as constructed, but it's overall a very accurate view of what they intended to build and actually did build. Thunder Mesa was there, too:

If you look carefully enough you can see the runaway train track heading down the side of the mountain.

No, they really were going to build this. It even sits perfectly along the bend in the river, the bend that was specifically carved out for it in 1971.

Come back for Part Two when we'll pry the lid off that building and take a ride on the Western River Expedition!

Western River Expedition Series: Part One | Part Two | Part Three

Do you enjoy long, carefully written essays on the ideas behind theme parks, like this one? Hop on over to the Passport to Dreams Theme Park Theory Hub Page for even more!