If you're looking for the ultimate journey through Pirates of the Caribbean - the history, the attractions, the films, all of it - check out my new book Scoundrels, Villains & Knaves. You'll never think of the classic ride the same way again.

"[This is] the beginning of an entirely new form of art and entertainment which will eventually take its place beside the theater, opera and motion pictures." - Walt Disney at the 1964 World's Fair

"It's better than the movies. Pirates of the Caribbean, the 40-year-old Disneyland ride, is better than the hit movies it spawned. Also, it's better than more than half the rides in the Park, better than half the movies you've ever seen, better than half the moments in your life, and perhaps better than at least half the sex you've ever had. Everybody has their off days. POTC is such an impeccably awesome attraction that there's really no point to my writing about how awesome it is." - Geoff Carter, Your Souvenir Guide

A Personal Admission

It's been put off for long enough.

As a critic and commentator, there are certain "holy mountains" one is expected to scale at least once. In writing about film, for example, a confrontation with "The Birth of a Nation" (1915) is both ritualistically expected and necessary, not only because it is a landmark film but because it is one of those moments where everything about the cinema crystallizes into one coherent moment in time. Because it's impossible to ignore Griffith's film, one must grapple with it and, inevitably, find oneself both desiring and fearing the process.

Pirates of the Caribbean is the "Birth of a Nation" of themed design, the moment where the concept of a ride through attraction that began so humbly and so long ago - as metal cars scooting along on tracks in darkened rooms - finally crossed over into the rarefied world of art. It is the moment where everything about themed design and what is possible in it crystallized into a single master stroke of an attraction, still the one to beat all these years later. In 1967 it plumbed new depths of the possibilities of a theme park attraction. It created the public perception of a Disney attraction as a lavish, lar

ger than life spectacle. It was Walt Disney's final project. Riding it is like going to church, that's how strong the tidal pull of fascination it exerts is. It may as well be a national monument. Other attractions may have more superlatives to their names: Haunted Mansion may be more rich in fascinations; Horizons may be more ambitious and complex. But there is nothing like the original version of Pirates of the Caribbean, at Disneyland or anywhere else. It is unquestionably the greatest attraction ever made.

ger than life spectacle. It was Walt Disney's final project. Riding it is like going to church, that's how strong the tidal pull of fascination it exerts is. It may as well be a national monument. Other attractions may have more superlatives to their names: Haunted Mansion may be more rich in fascinations; Horizons may be more ambitious and complex. But there is nothing like the original version of Pirates of the Caribbean, at Disneyland or anywhere else. It is unquestionably the greatest attraction ever made.

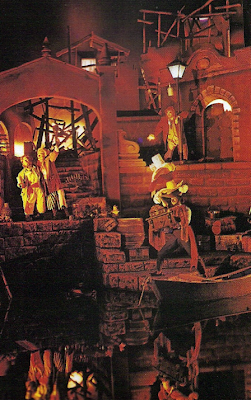

(Image at right from Daveland)

And with that comes a problem, which is that in the high regard we give it, it often seems unapproachable. Certainly, even on this site beyond a few call-outs to it as a touchstone experience, I have resisted going too deep down the flume into the subterranean areas below. Despite this I will admit that Pirates of the Caribbean at Disneyland was the galvanizing experience that compelled me to begin to think critically about a themed design experience; in that way it both changed my life and means that much of the writing on this site rests uncomfortably in its long shadow.

On another level it also means that I'm not sure even a full size book on the subject could fully expunge all of the brilliance contained in the attraction. It's like King Lear; it is one of those monumental works you could spend your entire life studying. So this essay is also, in a way, doomed to inadequacy. There is simply no way to fully account for Pirates of the Caribbean in one article. I shall combat this not by trying to tie together everything brilliant about the attraction in some sort of master thesis the way I did with the more prosaic Orlando version, but by presenting a collection of different approaches to individual components of the ride. In doing so, however, it means this essay must come with a caveat:

If you have not experienced the Disneyland, 1967, full strength version of Pirates of the Caribbean, please do not read this essay, because I will ruin the ride for you. Such a dynamic work needs to be experienced with a fresh mind instead of through the lens of an academic "reading", which is what I am about to attempt. Please preserve this wonderful experience for yourself.

Okay, then: I have a final admonition in this preposterously extended prologue.

For those of you playing along at home, it may be worth noting here that this essay is intended to sit alongside my piece about the Florida Pirates of the Caribbean, but in reading both one may note that my message is somewhat conflicted, in that elements I highlight as strengths of the California show in the text below are the things I praise the Florida show for eliminating. I'm not being hypocritical; I'm recognizing that both attractions are unique entities that play by different rules. While I don't think this is a bad thing it does contribute greatly to the misunderstanding and scorn the Florida Pirates receives. Because a California native imposes a "West Coast Reading" on the East Coast ride doesn't mean that the designers had any such inclinations in mind. The rides do, after all, have unique strengths and weaknesses.

For example, to call out an example from another attraction, Disneyland natives almost universally praise the trim exterior and stately entrance room of the Disneyland Haunted Mansion because it

means that the attraction only becomes strange and "haunted" when the elevator begins to descend in the stretching room scene. That's undoubtedly a powerful moment but the Florida version simply doesn't have it; there's a bat weather vane on the house outside, a howling ghost dog, and an aging portrait in the entrance area. These aren't weaknesses of the Florida show, it just means that it is doing something different.

means that the attraction only becomes strange and "haunted" when the elevator begins to descend in the stretching room scene. That's undoubtedly a powerful moment but the Florida version simply doesn't have it; there's a bat weather vane on the house outside, a howling ghost dog, and an aging portrait in the entrance area. These aren't weaknesses of the Florida show, it just means that it is doing something different.

What all of this means to say is that Pirates of the Caribbean, more than almost any major canon Disney ride, indicates that there is no single "right way" to do themed design; there is no single platonic solution that solves everything, even when one version of the sum total effort achieves near perfection. Some strict design elements in this, the greatest attraction ever made, were later straightened out and improved, and they happened for the 1973 "inferior" model. This itself proves the fallacy of comparison, the uselessness of playing that age old game.

I say we let each work stand or fall on its own strengths or weaknesses, because the integrity of the individual art piece is, in the long run, far more important than its place in a canonical progression of the history of the form.

Influences

If sailor tales to sailor tunes,

Storm and adventure, heat and cold,

If schooners, islands, and maroons,

And buccaneers, and buried gold,

And all the old romance, retold

Exactly in the ancient way,

Can please, as me they pleased of old,

The wiser youngsters of today: so be it.- Robert Louis Stevenson

Pirates of the Caribbean is its own national myth.

Pirates of the Caribbean is its own national myth.

It was born relatively recently - 1967 - but it has become as eternal as George Washington and his apple tree and the stories of Johnny Appleseed. In other words, it has become a popular legend, perhaps moreso than any other Disney product. Walt Disney Studios has spent much of its life enshrining American myth and legend, in doing so replacing the original with the popular art incarnation of it in the public imagination, but in one of Walt Disney's final acts he created his own national myth, stitched together from castoff bits of cultural debris, and in the last forty-five years it has gained an astonishing amount of cultural currency.

Yet this final, penultimate success was not won on the shoulders of any one recognizable established cultural figure, not in the way that, say, the Great Moments With Mr. Lincoln show piggybacks on the American obsession with the sixteenth president. Instead, Pirates of the Caribbean draws from a more ethereal set of influences and thus seems to be the zenith of the entire cultural concept of high seas piracy. This accounts for its cultural longevity, perhaps, even as works like Treasure Island and Captain Blood seem to echo down through those caverns. It reminds us of them but also seems to sum them up, to synthesize everything about those pieces into a whole which draws upon our collective unconscious even while breaking expectations and forming new ones. Because it is original yet draws on every trope and tradition of pirate lore possible, Pirates of the Caribbean supplants them all as the definitive popular culture text on piracy currently in circulation.

"When Walt was talking about this, the first thing I did was to get a few books on pirates. You know the artist who really invented pirates as we now see them was an illustrator by the name of H.C. Pyle. I have some of the old books with his illustrations. He was the guy who really decided how pirates should look..." Marc Davis, The E Ticket, 1999

"We do try to use the material that's in [pre-existing films] because people know it and recognize it. It helps a great deal to have something that they already know." John Hench, Disney Family Album, 1984

"I knew a lot about pirates, having lived down on the Gulf Coast. I lived in Galveston, Texas, where there was a lot of interest in pirates, and locating pirate gold. Somebody was always trying to find Captain Kidd's treasure around there, you know." Marc Davis

The search for pirate gold is one of those myths that refuses to die. Its roots surely predate Mark Twain when he wrote of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn marauding downriver and lifting the plundered gold from Injun Joe's Cave, although that may have been the text, along with Treasure Island, which most strongly fixed the image in the minds of the generation of artists who built the attraction, Walt Disney amongst them. Truthfully, the buccaneer gold business been going on for centuries now.

The search for pirate gold is one of those myths that refuses to die. Its roots surely predate Mark Twain when he wrote of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn marauding downriver and lifting the plundered gold from Injun Joe's Cave, although that may have been the text, along with Treasure Island, which most strongly fixed the image in the minds of the generation of artists who built the attraction, Walt Disney amongst them. Truthfully, the buccaneer gold business been going on for centuries now.

Besides Captain Kidd, who buried treasure up and down the east and gulf coasts of the popular imagination, there was Thomas Veal, who entered a cave known as "Dungeon Rock" in Massachusetts to retrieve a hidden hoard and never came out. He was likely buried alive with his gold in the New England 1658 earthquake, making Veal a deep source for Davis' famous Treasure Scene in the mystery caverns. One man, Hiram Marble, spent sixteen years and his entire life's savings digging into Dungeon Rock looking for Veal's motherlode. And of course Blackbeard has kept the citizens of North Carolina busy for generations looking for his ship and/or riches.

"I got a call from Walt and he wanted me to do a script for the pirate ride. I'd never done any scripting before. I'd worked in the Story Department, mostly as a sketch artist. But I said, 'Oh, all right, I'll give it a try.' So I put on my pirate hat, dug out a bunch of pirate books, and watched Treasure Island." X Atencio, Disney News, 1992

These are very strong inherited images, and the American tradition of searching for pirate gold (these are pirates of the Caribbean, not the Atlantic), informed by the evocative images supplied by Louis Stevenson, of Ben Gunn's caves and the skeleton of Allardyce, the human compass, combined to create the "mystery caverns" which begin the attraction proper. Indeed, we would be surprised to not find pirate gold down in those caves, and the attraction (at least in California) does not disappoint. This sequence exploits our pre-existing cultural knowledge of piracy to achieve its effect.

"..At the beginning... I was taking the pirates that were real from history, like Morgan, Captain Kidd, and Blackbeard. These guys would shanghai somebody and force them to become a member of the crew. They would have to sign the articles with their own blood. [...] Most pirates died of venereal disease that they got in bawdy houses in various coastal towns. I was sorry to read that because it took a lot of the glamor out of these characters. So at first I wanted to explore the possibility of using real pirates in the show, but later I decided that that wasn't the way to go." Marc Davis

"[Walt Disney] didn't like the idea of telling stories in this medium. It's not a story telling medium. But it does give you experiences. You experience the idea of pirates. You don't see a story that starts at the beginning and ends with, 'By golly, they got the dirty dog.' It wasn't that way." Marc Davis

In the way that the final attraction draws less on specific influences than it allows you to "experience the idea of pirates", in Davis' succinct phrase, it simultaneously shrouds itself in myth to the point where it seems like it may have always existed. The first thing presented in the attraction's entry area is a beach strewn with a map, treasure chest and jolly roger as if to hint that treasure may be buried below - a visual abstraction of our conception of lost pirate gold. Behind it, a cascade of leaves forms a curtain which seems to shroud the rest of the attraction from view. Along the walls are painted Davis' abandoned concepts for historical pirates. This simple, mostly bare room - which features little more than a boat channel, a bit of queue and the aforementioned simple scenic elements - seems to summarize everything one may expect to see in a pirates ride right off the bat: "Here's all the icons in one place, now watch us do something else."

And they do, of course. With the obligatory imagery out of the way, Pirates of the Caribbean succeeds as a riff on the entire cultural concept of pirates and seems wholly original yet still familiar as if we knew of it all along. Indeed, as proof, there are few people today who don't seem to secretly believe that X Atencio's famous "Yo Ho" song isn't an authentic sea shanty.

And yet in another way the simplicity of the entry room has another effect, one probably unintentional: it is like a bare stage on which the essential props of the drama are placed before the audience, or the opening statement of the magic trick that frames the rest of the illusion. You enter a building; you are inside... but not. In just a few meters, inside space becomes outside space and day is twisted into night. It is one of the essential magic tricks in the themed design lexicon yet that simple opening chamber frames the whole trick and grounds it in reality. Even as it provides the basic elements of a high seas adventure it's the setup for the illusion to follow.

Unraveling the Mystery

"My primary concern is that none of this material was 'Disney.'" - Marc Davis

There are drawbacks to this cultural familiarity, however, which have obfuscated certain parts of the attraction and diluted their impact. One of these facets which we risk losing sight of is an attraction which poses its action as a parable which is told as a mystery. The pirates will all perish in the burning city or else each others hands after the treasure has been lifted; these men are doomed. We only come to their story by little, tiny remnants which may be pieced together in retrospect.

Consider how the Disneyland attraction withholds its pirates for an astonishing length of time; we enter the attraction with the promise of pirates and signs of their presence are all about; following the very first drop we now hear the pirates singing and expect them to be around the next bend. We do find them after another waterfall, but they're dead. It should be a sobering moment in an attraction which promises pirate frivolity.

As the first major scene in the attraction proper, as the first sign of pirate life we've yet seen, Dead Man's Cove offer only death and decay and establishes the grim morality play to come. Because we know the brigands can never outrun this fate as ghosts and ossified bones, it casts a long shadow over the attraction. This is the necessary editorial perspective, why it is possible to frame the debauchery that follows as actions that will have consequences. It is a judgement, and it should be a bucket of ice water in the face to any rider paying close attention.

As the first major scene in the attraction proper, as the first sign of pirate life we've yet seen, Dead Man's Cove offer only death and decay and establishes the grim morality play to come. Because we know the brigands can never outrun this fate as ghosts and ossified bones, it casts a long shadow over the attraction. This is the necessary editorial perspective, why it is possible to frame the debauchery that follows as actions that will have consequences. It is a judgement, and it should be a bucket of ice water in the face to any rider paying close attention.

One of the great strengths of the Disneyland ride is the looping rising action which seems to be constantly cheating towards the primary action from odd angles, always teasingly oblique. For an attraction with such a strong, exciting name as "Pirates of the Caribbean" that it can now be used to market action movies, the show spends forever moseying about the periphery of the concept. We begin in a nighttime bayou under a sign that only vaugley hints at what's to come - Laffite's Landing - before we're off into the bayou and the mystery begins. Why are we here and where are the pirates? Over the years, thanks to the internet, it's been very easy to find speculation that the "old man on the porch" scene in the Blue Bayou represents Jean Laffite himself. Of course this is nonsense, but it's nonsense we can learn from.

Where are the pirates and what is the bayou? The name itself is our clue here, for the name "Blue Bayou" was not accidental and does have an precedent in the world of Disney.

What is the Blue Bayou? It was the name of an animated short intended to be part of Fantasia, originally meant to accompany "Claire de Lune". Because Fantasia was so long, it had to be excluded, but Disney finished the thing anyway in 1942 and sat on it for four years, finally releasing it with new music by the Ken Darby Chorus as part of "Make Mine Music". Yep. But when you watch Make Mine Music, what's the very first thing that shows up onscreen during the "Blue Bayou" segment? A title card reading: "A Tone Poem".

That's the key: the Disneyland Blue Bayou is a tone poem, a throwaway loveliness that opens the heart more than it develops the action. It is a necessary prelude to the attraction that follows because it sets up the central mystery by deferring our expectations. Where are the pirates? The first person we see on the ride is the old man in the bayou; could he be a pirate? The ambiguity lingers in our minds. The Bayou serves the same purpose as the opening title crawl at the front

of a film: it is the buffer between our reality and the nocturne to follow at the same time that it raises a central mystery and a growing sense of unease. It allows us to calm down, get settled in, and look and listen; to truly absorb.

of a film: it is the buffer between our reality and the nocturne to follow at the same time that it raises a central mystery and a growing sense of unease. It allows us to calm down, get settled in, and look and listen; to truly absorb.

This is a neat trick because following the Blue Bayou, we come across maybe the best hundred feet of track ever put into any themed design show ever, and what's most amazing is how this is accomplished with essentially nothing. Just as the entry room acted as the attraction's overture, expressing central themes, and the Blue Bayou is the prelude to the strum und drang to follow, a mood of quiet contemplation and anticipation rather quickly gives way to dread as we pass through the brick arches into the darkness. Now, suddenly, there is almost nothing to look at or hear as the bayou sounds fade away and are forgotten. Now, it is one thing for an attraction to promise Pirates and not immediately deliver; it is another to not even offer scenery to admire as we press on into the darkness. The questions loom larger.

Here Pirates of the Caribbean accomplishes something no other attraction ever has, to my knowledge: it utilizes a whisper in the darkness. As both eyesight and hearing fail us in the dark tunnel, we slowly hear and then, by dint of its solitary nature, strain to resolve a human voice seeming to speak barely above a mumble. Our senses effectively reduced to just one, we latch onto that voice and narrow our focus onto it like a laser. Who is speaking? Will it be a hero or a villain? The design of the tunnel adds the unsettling dimension of making it impossible to guess from whence the voice issues: is it in front of us, or behind us, or to the side? Surely, now, we will encounter the Pirates of the Caribbean.

This is pure gothic horror stuff. A whisper in the darkness is just the sort of thing you never want to hear late at night when your defenses are at their lowest ebb. There are abstract visuals to confuse us as we move through the darkness: an unexpected lantern, a door and a window that seems to promise some logic to this deepening dream. Just before, as a sort of setup we saw the old man rocking outside of his apparently inhabited cabin, the only human characters we've yet encountered, but the pattern betrays us. The voice does not speak from beyond the door; there is nobody home, and as we turn the corner we discover that the voice issues from something that can hardly even said to be human. It's some sort of ghoulish apparition, a disembodied head issuing confusing commands at the apex of the very last brick arch. The mysteries deepen and now have tipped over into what is unambiguously a ghost story and, like Alice, we are pulled down the rabbit hole deep into our unconscious.

The drop leads to a cavern where we expect to find the pirates once again, but once again we are deceived; the buccaneers have rotted away; all that's left are their voices. Even those betray us, as the rousing song becomes an echoed warning that "dead men tell no tales", that the dead will not give up their secrets so easily. The cavern itself is interesting in how quickly it establishes an understanding that we are now under the city; roots push through the ceiling and as jaunty as the song is, the setting is even less reassuring than before. The memory of that fades with the second drop. The attraction has at this point thoroughly demolished our expectations: day has turned into night, inside has turned into outside, pirates have turned into ghosts, and we are now not even sure of where we are.

The drop leads to a cavern where we expect to find the pirates once again, but once again we are deceived; the buccaneers have rotted away; all that's left are their voices. Even those betray us, as the rousing song becomes an echoed warning that "dead men tell no tales", that the dead will not give up their secrets so easily. The cavern itself is interesting in how quickly it establishes an understanding that we are now under the city; roots push through the ceiling and as jaunty as the song is, the setting is even less reassuring than before. The memory of that fades with the second drop. The attraction has at this point thoroughly demolished our expectations: day has turned into night, inside has turned into outside, pirates have turned into ghosts, and we are now not even sure of where we are.

So as we pass the bleached bones of the brigands, the mystery and ghost motif kicks into high gear; most all ghost stories are mysteries, after all. Discover the reason the ghost is here and the dead can be sent back to their rest and the natural order restored. This works for everyone from Pliny the Younger, through to Shakespeare, and on to Stephen King. We the audience become investigators, looking to clues amongst the detritus of the pirates underground stronghold as the mood shifts from mysterious to foreboding to darkly comic. The skeletons are faintly funny, their human-like positions and activities only pointing out their status as corpses ever more clearly. They drink rum, they count money, and a piano plays itself, obviously typical ghost business: the same gag was used in the Florida Haunted Mansion just a few years later and the instruments even look similar.

The caverns themselves speak as eloquently and essentially subliminally. The mere act of plunging underground into a cavern carries with it a wallop of associations which play on us just as strongly today as they did on their creators in the 60s. We not only bury our dead in the ground but we know from a host of literature from Plato to Dante to Milton that the underworld is down there, too. Like Orpheus, we will confront the dead. And just as Dante's inferno was more about Dante's soul than the blazes around him, we perhaps can expect to uncover hidden truths in this pirate underworld. The descent underground and twisting path through the caverns is as surely into our own subconscious dream state as it is to any place literal. The caves ultimately cannot be localized under the city of New Orleans or any other place because they are our one step beyond: underground, apparently open to the ocean, full of water, storms, falls, beaches, bones and dust. Lulled into accepting this impossibility, we are prepared for the next.

And then we reach the attraction's first climax, the treasure horde, which is positioned last in the sequence not only to send the "mystery" sequence out on the strongest visual but to give us the impression that we've found the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. Immediately after this visual, the attraction shifts tones for the fourth time as we apparently travel back into history through yet another dark tunnel with echoing voices to finally find the answer to the question of how the pirates met their doom.

And then we reach the attraction's first climax, the treasure horde, which is positioned last in the sequence not only to send the "mystery" sequence out on the strongest visual but to give us the impression that we've found the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. Immediately after this visual, the attraction shifts tones for the fourth time as we apparently travel back into history through yet another dark tunnel with echoing voices to finally find the answer to the question of how the pirates met their doom.

I make much of the fact that X Atencio wrote narration for each of the scenes in the "Lower Grotto" sequence, but these narration pieces were never used. The scenes are rich in fascinations, from the ghostly sounds of revelry which still echo through the underground bar to the weird Victorian decor of the Captain's Chamber, and of course the images are self explanatory without really explaining much. We've arrived too late: dead men tell no tales. The ghostly voices which send us back in time are the very first pieces of expository narration we've yet heard and the attraction is by now nearly half over.

All of this leads up to the Bombardment Bay scene, a suitably epic first movement for the show's second act, and it is impressive no matter which version of the show we see. But no other version spends a full six minutes preparing us for it by making us complicit in the act of getting there, six minutes full of intrigue, ghosts, and a mute chorus of rotted bodies. No other version denies us the pirates again and again, luring us deeper and deeper into the dream state until we find them in their ship, cannons blazing, as iconic an image of piracy as was ever presented. One of the things which makes Pirates of the Caribbean great is how it refuses, again and again, to manifest the very reason it exists, how slowly the petals open to reveal the flower, how gradually the icy grip of death yields its secrets. It is as perfectly orchestrated an opening to an attraction as has ever been devised. In six perfect minutes a high seas adventure becomes a ghost story that becomes a mystery and back again. By framing the main action as an investigation into history of a group of doomed men, the mantra "dead men tell no tales" never fades from our minds.

Circularity

It can be argued that the Bombardment Bay scene is like a hinge that the rest of the show pivots around. It is more or less the midpoint of the ride and, like most hinges, its action is symmetrical. We have been brought from a state anticipating piracy and adventure to a state where we are like crime scene investigators, trying to piece together the story from some time in the future. It is an enormous act of drama to bring us back in time to the "scene of the crime", then. We've spent the first half of the show watching the pirates materialize out of nothing, becoming skeletons and then flesh and blood, and from the Bay scene onwards we now watch them fade away back to skeletons. We anticipate and foreshadow the act of destruction then watch itself play itself out, bringing us back to where we started.

Act Two of the show climaxes at the burning city; this is the pirates' biggest moment of triumph and revelry and, following the rules of classic drama, it is also inevitably the moment where their fortunes turn. If the Blue Bayou is the Overture and Prelude and the Act One is the mystery Caverns, Act Two can be seen as the "major action", the sequences the ride is built around. This act ends when we pass out of the burning city and into another dark tunnel for a short Act Three: Inferno. Fire symbolically destroys as it purifies, and we don't need any indication other than those swaying timbers and thundering silence that the crew has begun to perish in the flames. A circle is starting to close.

Act Two of the show climaxes at the burning city; this is the pirates' biggest moment of triumph and revelry and, following the rules of classic drama, it is also inevitably the moment where their fortunes turn. If the Blue Bayou is the Overture and Prelude and the Act One is the mystery Caverns, Act Two can be seen as the "major action", the sequences the ride is built around. This act ends when we pass out of the burning city and into another dark tunnel for a short Act Three: Inferno. Fire symbolically destroys as it purifies, and we don't need any indication other than those swaying timbers and thundering silence that the crew has begun to perish in the flames. A circle is starting to close.

This circular nature is one of the greatest pleasures of the attraction, one of the things that makes it as great as it is. In the mid 90s there were a number of additions which made the circular plot even more apparent, adding skeletons to the final scenes and a reprise of "Dead Men Tell No Tales", but in a way these were redundant. We understand on some unspoken level that the spell is reversing itself when we take that long, chugging ride back up the lift hill back to the bayou, it's an understanding beyond phrase or comment. We move up after having moved down and return to our point of embarkation, the musical Overture returns, the Bayou once again reasserts itself.

In this way Pirates of the Caribbean may be the only attraction to ever utilize its structural resources as an attraction effectively. The Blue Bayou and Laffite's Landing are not just locations of the load and unload zones, they are signifier of our journey. Literally everyone who gets on the ride sits down and looks up at that sign:

Ever wonder about that sign? Maybe, why it's there? It is there because it makes the Load zone into a location, it fixes it in your mind. It's even a neat little alliteration, all the better to help you remember it. You're not just getting on a boat, you're getting on a boat at Laffite's Landing, dammit. When you return to that sign, a very satisfying sense of closure comes with it, a closure which helps point to the attraction's circular nature. Laffite's Landing may be the most important attraction load area ever because of that sign and the circular structure it points to.

Make no mistake: all attractions, no matter how sophisticated, inscribe a circle, for specific, technological reasons. But no other attraction tells a narrative that is a circle while inscribing that circle, allowing us to connect meaning (narrative) to form (a boat moving in a channel). Pirates of the Caribbean is that Wagnerian aesthetic of the total synthesis of all the works of art into a single statement, the Gesamtkunstwerk. Other attractions may have separate load and unload areas and encourage us to see ourselves starting at one location and proceeding to another, different one: the Disneyland Haunted Mansion does this very effectively. But these attractions seek to obscure their circular nature, in Pirates of the Caribbean, that nature is given meaning and form.

The events of the attraction happen in the past and are surrounded by signifiers that foretell their conclusion: the Pirates of the Caribbean will always perish at each others' swords. This is an event we can replay over and over again and access through a magic window, a portal to another time, a brick arch in the corner of the bayou that brings us somewhere new and nowhere at once. Attractions seek to create the illusion that what we see happens spontaneously, unpredictably, but not Pirates of the Caribbean, it is an impassive procession of a doomed history. Every time we ride the Haunted Mansion, or Mr. Toad's Wild Ride, or Snow White's Scary Adventures, there is an implicit "reset button" that gets pressed so the story can unfold its narrative from A to B again. Pirates of the Caribbean starts at A, goes to C, then back to B, then on to A. There doesn't need to be an excuse that the same thing happens every time you ride it because the events of the past are as fixed in time as that skeleton pinned to the wall of the cave.

Visual Patterns

The visual treatment of the attraction can be our clue to appreciate this. If we accept the understanding I've posited that the attraction depicts an event of the past in a fixed cycle of destruction and it does this by bringing us back in time to replay some deep, unresolved trauma which still haunts the caves, then there must be some visual indication of this, no matter how subtle they may be. Some of the best art is created more or less unconsciously, and as similar efforts have gone forward to reveal the hidden concepts structuring the Haunted Mansion, we can find the same sort of thing within Pirates of the Caribbean if we peel it apart.

We have already established the myriad purposes of the entry room, with its plain windows and plastered walls. It challenges us out of the "reality" of New Orleans Square to introduce signifiers of "the idea of piracy" and thus provides the visual overture to the attraction. There is another purpose, too, and since this simple room is the very first architecture we see that wholly "belongs" to the attraction, it's worth examining closely.

It is, primarily, an empty room with a boat channel running through it; the boats are returning to Laffite's Landing from the attraction. On both sides of the channel are arches, and the channel hugs the small island on which are placed the lanterns, chest, map etc discussed above. Behind these items is the "leaf curtain" that shrouds the Bayou. In this way we can see the return loop of the boat channel as a line dividing New Orleans Square from the Bayou and, thus, the "reality" of the square from the supernatural mystery it conceals.

The arches indicate this. On the "square" side, nearest the entry doors, they are tall, thin poles with wrought iron brackets and details from which are hung lanterns in the Old French Quarter style. They "belong" to the Square. On the "Bayou" side are strong, sturdy brick arches through which the Bayou may be glimpsed.

Arches of this style are visible elsewhere in New Orleans Square...

..but only in Pirates of the Caribbean do they attain their unique symbolic power. Those arches are the magic portals that allow us to access the mysterious night of the Bayou. It is only when we walk through one of them alongside the boats...

...are we transported into the fantasy forever-night of the bayou itself. Notice how the texture detail of the walls is different on each side of the arch in the photo above? These arches are a simulated sunset; as we move through them away from the brightly lit, windowed "Overture" room, we make our supernatural crossing into the bayou and, only then, can the story begin.

Here's a diagram I worked up based on a fanmade blueprint downloaded from Flickr user Enfilm (which is an amazing resource, I may add). It's not really accurate but it does show how the two kinds of arches in this entry room divide "daylight" (tan area) from the "nighttime" of the bayou (dark blue area).

Notice how WED could have elected to make those windows looking into the Foyer false windows or black them out, but they let daylight in anyway: this is all part of the showmanship of the Bayou illusion. It's a better trick if during the day that first room is flooded with Southern California sunlight. The green dots represent the wrought iron poles, the "New Orleans Square" arches, and that thick red line is the brick arches which divide day from night. The light blue boat channel moves between these. That brick arch we pass through is right at the solid black line dividing New Orleans Square from the dream state of the ride.

The arches return, past the old man once we are deep into the dark heart of the bayou, and here they seem totally abstract until we remember their supernatural power to transform space before. Yet they've almost become totally abstract now:

All of this arch imagery comes to a head here:

This is literally the moment that the entire attraction has been building to, the reveal of the skull and crossbones, and as a frisson it is second to none. The skull is tellingly placed at the apex of the arch. This is where the keystone is placed; the wedge shaped rock which holds the arch together. Similarly this moment is the keystone moment of the attraction which holds it together: all those arches have been building away in the background, quiet signifiers of your progress towards the attraction's transformation into a ghost story. You've seen dozens of arches so far; but this last one, which leads to a drop and the inky darkness beyond, is the one that will do you in.

Arches recur elsewhere in the ride, of course, and are used extensively in the Second Act to divide the various scenes. But one in particular, right, is very close to the brick arches used to divide space in the Bayou; indeed it is one of our "Magic Portals". It's the arch that divides Act Two from Act Three, and it's another dark stone portal capped with a prominent keystone and darkness beyond. From this point in the attraction on, the arches begin to return, even as the town burns around them: the arch shaped cells in the Jail scene, for example. The arsenal is full of them, usually with fire licking just beyond, and as we escape up the waterfall and back to the Bayou and Overture, we pass through just a few more, marking our return to the present through a very prominent red brick arch. The circle closes.

Arches recur elsewhere in the ride, of course, and are used extensively in the Second Act to divide the various scenes. But one in particular, right, is very close to the brick arches used to divide space in the Bayou; indeed it is one of our "Magic Portals". It's the arch that divides Act Two from Act Three, and it's another dark stone portal capped with a prominent keystone and darkness beyond. From this point in the attraction on, the arches begin to return, even as the town burns around them: the arch shaped cells in the Jail scene, for example. The arsenal is full of them, usually with fire licking just beyond, and as we escape up the waterfall and back to the Bayou and Overture, we pass through just a few more, marking our return to the present through a very prominent red brick arch. The circle closes.

Attractions as Art

All of these things contribute to the greatness of the ride, but the above has by no means come anywhere near close to exhausting the interpretive possibilities of this great, great dynamic work of art. For example I have steered clear of discussing many of the town scene in Act Two, these are the scenes that the attraction is built around and so have received the bulwark of critical attention. But in a way, the strongest moments of the attraction are those between scenes, in the quiet moments, as we slowly drift into the darkness of the bayou and the whispering voice can get to us.

Or the leisurely rounding of a corner in the caverns as waterfalls splash around us to the left and right, or skeletal forms slowly materialize out of the darkness of a wind-torn ship. The uncomfortable quiet as we move under the creaking timbers of the burning city and are allowed to process the magnitude of the destruction. Or the almost full minute of darkness as we pass out of Act One and into Act Two, with no visual input whatsoever and the booming, taunting voices of the pirate ghosts echoing all around us. Pirates of the Caribbean may be the only theme park attraction to give us both time to regard it and then give us time to reflect on its brilliance in the spaces between scenes where things get very quiet and still. This surging push and pull between thrilling action and spectacle and quiet moments of reflection is what makes this ride such an indelible experience.

Yet that Prelude and First Act, they're so central to the attraction that they nearly eclipse the rest of it. When lifelong Disneylanders visit the Florida version of the ride, it's those scenes they object to missing, and it's not just because that's what's been removed, it's because they're the lifeblood of the attraction, in a way. As my friend Michael Crawford said after experiencing the full version for the first time: Pirates isn't better in California because it's longer, it's better because it's better. Every component is improved.

In a way, trying to do Pirates without the Bayou and Cavern sequence is like try to make Hamlet come off without the Ghost scenes. Yeah, the most famous scenes and quotes aren't in those scenes, but the Ghost of Hamlet is what makes the thing work, it's the little engine that the rest of the piece can trail behind. Temper with stuff like that at your own risk. Marc Davis had an astute eye for what worked and what didn't in themed design, and in a way, he was the very original student of the art which is what made him its finest practitioner. Davis shuffled a good deal of the ride around in Florida and Tokyo and he was the one who argued for a better Pirates in Florida, an argument he lost. For Tokyo Disneyland, though, he kept most of the start of the ride exactly the same as it had been in 1967. You can't improve on the perfect attraction.

Pirates of the Caribbean has given us many images, many famous moments. As such, I would like nominate my favorite thing in the attraction. It isn't what you would expect. Look off to the right.

These little forced perspective lighthouses appear in Bombardment Bay at the center of the attraction. I never get sick of looking at them because there's something about them that somehow encapsulates everything wonderful about the ride. They're there, off to the side, fun little details but you aren't really fooled by them. You know it's just an optical illusion but it never stops being fun to let yourself be tricked by them. And in another way, they're a perfect central image for the attraction and it is indeed serendipitous that they appear at the center of the show. Pirates of the Caribbean is the benchmark of all attractions, the one to measure up to, and so it's sort of like those lighthouses themselves. It's always there for you to come back to, always ready to be experienced again, it helps you navigate through life and art and by dint of its perfect construction is always richly rewarding. Pirates of the Caribbean is those little fires off in the night, somehow distant and close all at once. Always ready to help guide us home.

--

Emotional Map of Pirates of the Caribbean:

Entry Foyer = Overture

The Blue Bayou = Prelude / Pastoral

Haunted Grotto = Movement One

Transition Tunnel = Intermezzo

Sacking of the Town = Movement Two

Inferno = Movement Three

Up the Waterfall = Overture

--

Related Reading:

The Case for the Florida Pirates

History and the Haunted Mansion

5/11/11 - 8/17/11