It is entirely possible that when Walt Disney was overseeing the design of Disneyland, that he had no further thought as to the physical structure of the park other than it having a railroad around it. Indeed, this is one of the traditions which has been followed to the letter – whenever possible - by every generation of Imagineers, weather it be the oft repeated quote vis a vis the railroad or not. In a day and age when Walt Disney is deified beyond any possible comprehension and his most published quotes are treated like commandments from on high, even outside of the insular corporate structure of Disney, for the company to build a “Castle Park” without a railroad around it would possibly summon hordes of the faithful, heavily armed.

It is entirely possible that when Walt Disney was overseeing the design of Disneyland, that he had no further thought as to the physical structure of the park other than it having a railroad around it. Indeed, this is one of the traditions which has been followed to the letter – whenever possible - by every generation of Imagineers, weather it be the oft repeated quote vis a vis the railroad or not. In a day and age when Walt Disney is deified beyond any possible comprehension and his most published quotes are treated like commandments from on high, even outside of the insular corporate structure of Disney, for the company to build a “Castle Park” without a railroad around it would possibly summon hordes of the faithful, heavily armed.Yet there are other important structures to the parks too, beyond even the railroad, the railroad berm, a castle and a Main Street. Although we will probably live to see a Disneyland-style park without a Main Street, Adventureland, or Tomorrowland, there is one structuring formula which I guarantee will outlive any mutations of the original template: the waterways.

Water is such as essential, integral part of the Disney park experience, and smart design teams integrate water – weather it be placid or dynamic - in as many ways as possible in a park. Water, the basic element of life on earth, is bestowed with a magical capacity by human cultures, and it has appeared in a number of signifying forms through art and history.

Water’s depth and relative impenetrability can make it into a dangerous area, and deep sea lifeforms fit the human description of grotesqueries. Water’s dynamic and healing nature transforms it into waterfalls and ponds, places of renewal and contemplation, which culturally wormed its’ way into the European pleasure gardens and thus, through conceptual diffusion, into Disneyland.

Water, via its’ vastness and unclaimed nature, can be the setting for adventure and intrigue, and we have a deep-seated fascination with the ability of the Viking, the pirate, or the sailor to transverse these spaces.

Or water can be a transitory space, usually into limbo or death: human cultures of all races have referred to death as being thematically linked to water, probably since before we came up with the idea of a River Styx. Weather this be by dint of its’ links to vastness and loneliness, its links to our desire for peace and solitude in death, or its’ poetic repetitions of water’s role in birth, this is undeniable. Humans inevitably are drawn to tales of codes and morals being stretched to their limit on bodies of water. It’s one of our basic cultural tropes.

Well, it's fare-thee-well, my dear, I'm bound to leave you

Look away, you rollin' river

Shenandoah, I will not deceive you

Look away, we're bound away

Across the wide Missouri.

Oh, Deep,

Oh, my home is over Jordan,

Oh, Deep River, Lord.

I want to cross over into campground.

Oh blow ye the winds o'er the ocean

And blow ye the winds o'er the sea

Oh blow ye the winds o'er the ocean

And bring back my Bonnie to me.

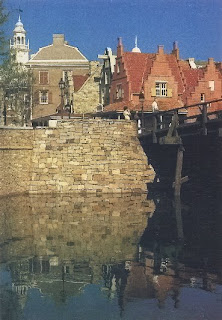

Disneyland’s use of waterways is really its’ most sophisticated unified technique of conveying otherworldliness. Although we may pass under a railroad train, that symbol of American progress and the country’s Manifest Destiny, we also pass over, under, and between waterways, which truly signal where the magical transformation of space begins. Although conceivably a holdover from a castle’s requirement to have a moat, we transverse bridges in order to enter the realms of Yesterday, Tomorrow and Fantasy. Those spaces not explicitly marked as passages over those magical waters are often designated as magical spaces through fountains, like those outside the Disneyland Tomorrowlands of 1955 and 1967.

Once inside those realms of fantasy, the water begins to play a subtly different role: as signifiers content through cultural cues. The Enchanted Tiki Room devotes a long time to a magic fountain, and right next door the murky (color coded: dangerous) waters of the Jungle Cruise transport visitors into the attraction, using the water’s dual cultural contexts of adventure and the fantastic to immediately create a visual, cultural, implicit understanding of the rules of the attraction. The Swiss Family Treehouse’s mastery of water is signified through the iconic waterwheel, a sign that in this attraction, man has both harmonized with and conquered nature through ingenuity. Compare this to Schweitzer Falls of the Jungle Cruise, created by nature and located at the center of an untamed wilderness, one of the original Disneyland signifiers of danger.

Fronteirland displaces its’ obvious and traditional symbol of the progress of the West - as the railroad has already been used at Main Street - and instead treats the river as a tamed beast by introducing a steamboat, a uniquely American invention similar to the railway engine. This is where Walt Disney’s intentions become somewhat more interesting: we know from the earliest drawings of his “Mickey Mouse Park” that a jungle river ride and a steamboat around an island were planned. This having been established, and taking into account the Tomorrowland lagoon and the submarine ride he finally built there, can Disneyland also be seen as a document of America’s mastery of water? Water voyages play into every original Disneyland land except Main Street and account for much of the park’s aesthetic cohesiveness.

New Orleans Square, the most thematically unified thing Disney ever has and likely ever will build, uses a number of visual tropes both inside and outside its’ attractions to signify a beautiful but haunted atmosphere, and the pallor of the deathly mystery of the sea hangs over all. Pirates of the Caribbean inverts the conquest of the water seen by the Mark Twain, Submarine Voyage, Jungle Cruise, Swiss Family Treehouse, and just about every other attraction by making the open water something genuinely frightening and dangerous: immediately we are punished for traveling too far into the bayou by a seafaring specter and sent into a phantasmal realm of evidence of the sea’s conquest of man. Although the dead pirates may have been done in by a variety of factors, the sound of seagulls and surf leave little doubt that they are, in fact, in a watery grave. Even the Haunted Mansion, with little explicit reference to the sea, has a ghostly pallor of the ocean over it, with its’ schooner windvane, widow’s walk, and ghostly changing portrait. Although WDI doesn’t make an effort to cue us on this, in both location and architectural style, both Haunted Mansions make more sense if we don’t think of them as being on a river, but an ocean.

WED, always conscious of visual tropes and how to exploit them, really did a masterful job of creating even further meaning through waterways in Florida. In order to reach the Magic Kingdom, spectators must first transverse a body of water, weather directly across or around the circumference. This is a much more meaningful exploitation of water than anything at Disneyland, as the act of going across water serves the double purpose of making the journey more picturesque, as well as saying, culturally, that by the time you’ve crossed the lake, you will be very far away from reality. By exploiting our cultural concerns with water, WED has set the stage for us to subtly but physically enter the dream state of The Magic Kingdom.

WED, always conscious of visual tropes and how to exploit them, really did a masterful job of creating even further meaning through waterways in Florida. In order to reach the Magic Kingdom, spectators must first transverse a body of water, weather directly across or around the circumference. This is a much more meaningful exploitation of water than anything at Disneyland, as the act of going across water serves the double purpose of making the journey more picturesque, as well as saying, culturally, that by the time you’ve crossed the lake, you will be very far away from reality. By exploiting our cultural concerns with water, WED has set the stage for us to subtly but physically enter the dream state of The Magic Kingdom.This probably would’ve been enough, but WED doesn’t rest on its’ laurels and every land in Magic Kingdom has important ties to the water. Adventureland’s most significant visual trope, given the mix and match architecture, is of water, and the moat was not extended to go around the Swiss Family Treehouse for no reason. Adventureland has seven picturesque waterfalls, three on Jungle Cruise, three on Swiss Family Island, and one in front of the Tiki Room. The soothing, dynamic nature of these waterfalls is still one of Walt Disney World’s most beautiful things today, and when Caribbean Plaza was added in 1973, it brought along five of its’ own tile fountains, each carefully but discreetly tucked away and each given its’ own name. No other land in the park uses cascading water as a key aesthetic feature.

Frontierland and Liberty Square brilliantly use the river as the key feature of the area, and as spectators follow the flow of the river, time passes and America pushes west. At the transition between Frontierland and Liberty Square, guests pass right over a key conceptual feature of this evolution: a small babbling brook which empties into the Rivers of America known as “The Little Mississippi”. Early guidemaps for The Magic Kingdom always included Frontierland and Liberty Square on the same page or logo to make explicit the link between the two as being a “meta-land” of American progress. This is why you can enter from the hub at Liberty Square, the start of the cycle, and not Frontierland.

Fantasyland and Tomorrowland and even Main Street’s use of water is comparatively simple, although Main Street at least had the sense to exploit the picturesque quality of Magic Kingdom’s beautiful, vast and winding moat and plop Swan Boats on it for a time. Fantasyland’s Submarine Lagoon was once the transitory space on the far east of Fantasyland into Tomorrowland, its fanciful Victorian metal presaging futurism. The Lagoon was matched on the other side of Fantasyland by the Skyway pond and waterfall, but besides a few fountains placed too erratically to qualify as true key aesthetic features, Fantasyland was parched. So was Tomorrowland, although at least in the early days water would cascade down those sleek white spires and into the moat below.

And water has retained its’ power, in EPCOT Center where great pools of water (originally) welcomed visitors to Communicore and Danny Kaye’s old opening day promotional film quip about feeling like Columbus upon seeing World Showcase points up a use of water both related to the Magic Kingdom’s Seven Seas Lagoon and thematically new and varied. Disneyland Paris and Animal Kingdom would make good use of waterways to break up land, and the dynamic use of water is one of the few saving graces in Disney’s California Adventure.

And water has retained its’ power, in EPCOT Center where great pools of water (originally) welcomed visitors to Communicore and Danny Kaye’s old opening day promotional film quip about feeling like Columbus upon seeing World Showcase points up a use of water both related to the Magic Kingdom’s Seven Seas Lagoon and thematically new and varied. Disneyland Paris and Animal Kingdom would make good use of waterways to break up land, and the dynamic use of water is one of the few saving graces in Disney’s California Adventure.Water and waterways, as symbols of power, enlightenment and leisure, from Japanese Koi ponds through European Monarchy’s fountains and ponds and moats, right up to Disney’s deployment of water and water fountains and pond and lakes at Walt Disney World (very few of the resorts, for example, fail to make use of some kind of body of water), water and waterways are some of the simplest, cheapest and most effective design tricks up Mickey’s sleeve. And unlike efforts to be hip and edgy, unlike efforts to build the future, and unlike efforts to chase after a market share, water is classically beautiful and water will always be effective.